The Battle for Long Island City: Brother Horatio S. Sanford’s Stand for Democracy

Mayor Horatio S. Sanford of Long Island City, New York.

Article by Brete Murphy

Born of ambitions, Long Island City was chartered in 1870 with the bold promises of factories humming, warehouses rising, new homes filled with opportunity. Its boosters imagined a rival to Brooklyn, a gateway to the future perched on the East River’s edge. But what lay before the fledgling city was not glory; it was grit.

The work was relentless and unromantic. Streets had to be torn open and raised out of the muck. A leaky, jagged shoreline demanded shoring before it could host industry. Fever‑ridden lowlands, buzzing with mosquitoes, had to be drained if families were to live there in safety. Crews cut trenches for sewers, hammered at piers, and struggled to steady the battered dock at Hallet’s Point. Even the river itself had to be bent to human will, reshaped to carry freight more safely past its wharves.

Here, progress did not begin with marble halls or boulevards. It began in mud and stone, hammer strikes and shovelfuls; the dirty, difficult labor by which ambition slowly hardens into a city.

So it was that Long Island City’s first mayor, the reform‑minded A. D. Ditmars, sought a second term in 1872, he found himself challenged by Henry S. De Bevoise. De Bevoise won, and his time in office quickly drew criticism for ushering in a rougher, Tammany‑style politics that seemed ill‑suited for a young community still finding its footing. Promises of steady progress gave way to grumbling over favoritism and heavy‑handed rule.

By the middle of his second term, those concerns turned into Investigations that exposed enough misconduct to cost Henry S. De Bevoise his duties outright. It was an early reminder that Long Island City’s lofty ambitions would not be pursued without controversy; that alongside the work of building streets and docks came the work, no less contentious, of building honest government.

Fast Forward to Mayor Patrick “Battle Axe” Gleason

Before turning to Horatio S. Sanford, one must first reckon with Patrick “Battle‑Axe” Gleason, the swaggering, sharp‑tongued boss whose grip on Long Island City politics was as notorious as it was unrelenting. For years leading up to the 1898 consolidation into Greater New York, Gleason loomed as both the city’s most dominant figure and its most corrupt, a man whose name became shorthand for the rough‑and‑tumble brand of machine rule that defined the era.

Early Rise and Mayoral Power

Patrick Jerome “Battle‑Axe” Gleason was the kind of figure who seemed larger than life. An Irish immigrant and Civil War veteran, he began his climb through Long Island City politics as an alderman in 1881. By 1887, he had leveraged local scandal into higher office, seizing on the presumed suicide of city treasurer John Morris in 1882 as evidence of deep corruption at City Hall, turning it into a rallying cry in his campaign for mayor.

Once in office, Gleason made it clear he had no intention of playing by the usual rules. He refused to surrender his alderman’s seat, instead fusing the authority of both roles and consolidating power across City Hall. Patronage became the currency of his administration; city departments were pressured, contracts were steered toward allies, and loyalty often counted for more than legality.

The lines between Gleason’s public duties and private interests blurred almost entirely. He invested in trolley lines that conducted business with the city and leased buildings of dubious value to the school system, enriching himself while holding office. Accusations of graft and kickbacks clung to his administration at every turn, making “Battle‑Axe” both a master of political survival and a symbol of the corruption that defined the era.

P.S. 1 in Long Island City, NY

Ambition and Public Works

Gleason was never shy about chasing projects the public could see, and remember. His crowning achievement was the construction of P.S. 1, a massive schoolhouse that still towers like a monument to his taste for the dramatic. Yet behind the brick and marble, the city’s books told a harsher truth: reckless spending and creative accounting that left the treasury thin and Long Island City’s credit limping.

In the boardrooms and factories, Gleason’s politics met mixed reviews. He maintained a wary, transactional alliance with industrialist William Steinway, whose influence shielded both the city’s fragile fortunes and his own manufacturing empire. But with other business leaders Gleason often sparred, his bluster colliding with their patience, straining the very partnerships that the growing city needed to survive.

Conflict, Standoff, and Return

Combative by nature, Gleason’s fiery temper became part of his public persona; so much so that he once landed in jail for assaulting a reporter. After losing the 1892 election to Horatio S. Sanford, he flatly refused to leave City Hall, setting off a drawn-out legal battle that ended with his forcible removal, a spectacle that splashed across the front pages. Sanford finally managed to take office in the spring of 1893, but Gleason’s grip on local politics did not vanish. True to form, he staged a comeback, winning election again in 1895 and serving as Long Island City’s final mayor until its consolidation into Greater New York on January 1, 1898.

Gleason and Tammany Hall

Gleason struck deals with Tammany Hall but never entered its inner circle. Instead, he lingered at the edges, studying its methods and reshaping them for his own use. What he built in Long Island City was a scaled‑down reflection of the great Manhattan machine—favor traded for loyalty, threats delivered as policy, and politics practiced as combat. After consolidation, Tammany shut Gleason out of the new five‑borough order, leaving him increasingly isolated. When he died in 1901, he left behind a reputation split in two: celebrated for his bold public works, condemned for the corruption and fiscal chaos that trailed his rule.

Why This Sets the Stage for Sanford

Sanford’s short and embattled tenure, from 1893 to 1896, played out amid the ruins left by Gleason’s turbulent rule: coffers stripped to the bone, contracts entangled beyond reason, and a civic culture that seemed to exalt spectacle over stewardship. In such a climate, his much‑heralded “stand for democracy” was no shining banner raised above the fray; it was a weary, day‑to‑day campaign to keep the lamps of government burning and the machinery of the city from grinding to a halt.

Political Reformer Horatio S. Sanford & A City Primed for Reform

Amid the political turmoil that gripped Long Island City in the early 1890s, Brother Horatio S. Sanford of Advance Lodge No. 635 stepped forward as an unlikely reformer, confronting Patrick Gleason’s entrenched machine and lending momentum to the call for cleaner, more unified governance. Far from an eager aspirant, Sanford had not pursued the nomination himself; it was the Jeffersonian Party that turned to him, seeking a figure of integrity who might steady the city in a time of disarray.

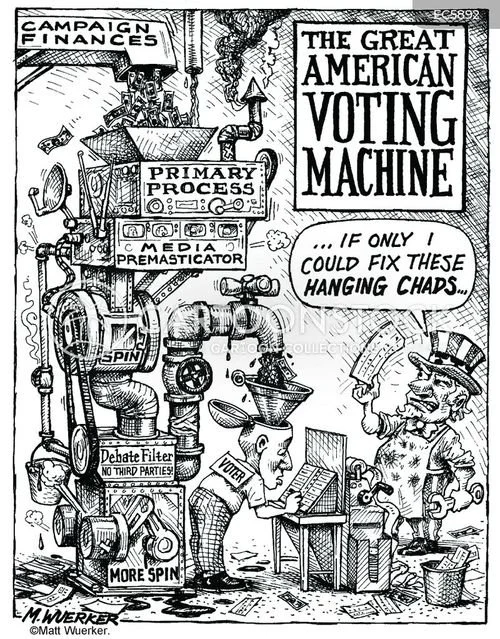

Press, Spectacle, and Machine Politics

Since its birth, Long Island City’s climb from marsh to manufactory moved like a pendulum; one swing driven by vision and enterprise, the next pulled back by opportunists compelled by avarice. Inching toward the glow of industry, progress came in hard‑won bursts.

For years, newspapers and dime‑store novels had whetted the public’s appetite with lurid tales from the fading frontier. In the restless years after the Civil War, readers devoured the saga of Wyatt Earp and others like him, stories where the line between lawman and outlaw shifted with the constant retelling; heroes one week, vigilantes the next. It’s little wonder, then, that Tri‑State papers framed Long Island City politics as a kind of Wild West drama of its own, fueling headlines with spectacle instead of substance and setting the stage for a reform candidate to step into the fray.

Seal of the Jeffersonian Republic Club of the Borough Queens

A Reluctant Candidate with Civic Roots

In 1892, the Jeffersonian Democrats placed their hopes in Horatio S. Sanford, a distinguished Manhattan businessman and proud Ravenswood resident, who seemed to personify integrity at a moment when the city needed it. To allies and observers alike, Sanford appeared almost tailor‑made for the task ahead: competent and steady, anchored in the community, untouched by the hunger for power that seemed to poison local politicians, and unwavering in his devotion to Long Island City’s future.

On the Jackson Avenue Improvement Board, he had already shown what vision in action could look like, pressing for running water and other modern necessities that eased daily life. To many, these efforts were not mere improvements, but the first markers of progress: the kind of practical, and hopeful steps that would lead the city toward prosperity.

The 1892 Election: Ballots and a Court Fight

Sanford accepted the nomination and squarely stepped into the ring with “Boss” Gleason, whose once‑unshakable regime was already staggering under scandal. On election night, the tide seemed to turn; early returns pointed clearly to a Sanford victory. But the celebration was short‑lived. The real battle wasn’t at the ballot box; it was in the back rooms where Gleason’s machine still held sway. City Clerk Thomas P. Burke, one of Gleason’s most loyal appointees, quietly rewrote the outcome. Ballot after ballot cast for Sanford was discarded on the thinnest of technicalities, while equally flawed votes for Gleason sailed through unchallenged. With the “corrections” made, Burke rushed the doctored tallies to Judge Daniel Noble, an Advance Lodge Brother, who, none the wiser, dutifully certified the results.

Then came the spectacle. Avoiding the storm, and legal obligation, at City Hall, Burke vanished. He barricaded himself inside his Greenpoint home, dodging deputies, and dragging out the transition by sheer evasion. Reporters hounded his doorstep; police trailed his movements. In one bizarre turn, they even intercepted him as he tried to slip across the East River and out of the city altogether. By the time the dust settled, Burke’s maneuver had handed Gleason a contested majority. But if the machine thought it had secured another easy win, it was mistaken. The outrage was immediate and furious: citizens poured their anger into the streets, the press thundered with accusations, and the courts became a battlefield. For weeks, the question of who truly governed Long Island City hung in the balance, the drama gripping the public like a serialized scandal played out in real time.

Why It Mattered

Sanford’s stand, rooted in civic reform rather than machine patronage, shaped LIC’s final pre‑consolidation chapter and offered a contrasting model of ethical leadership in a city hungry for it.

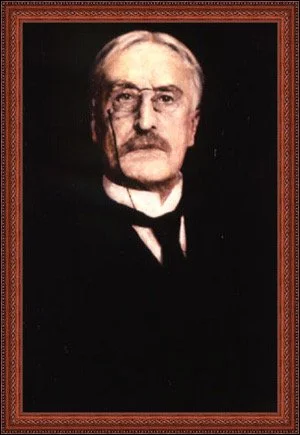

Mayor Patrick J. Gleason

Gleason Tries to Shield His Clerk

Patrick J. Gleason was back in the thick of it as accusations swirled around his city clerk, Thomas P. Burke, who had allegedly botched certification of the vote for mayor‑elect Horatio S. Sanford. Unmoved by appearances, Gleason tried to insert himself into the grand jury proceedings, claiming he could be impartial despite having benefited from Burke’s disputed certificate; an audacious move that set up a courthouse showdown.

When District Attorney John Fleming rose in objection, Gleason met him head‑on, sparring in a heated exchange that quickly became the talk of the courthouse corridors. The spectacle only deepened suspicions that the mayor was less an impartial officer of justice than a partisan fighter intent on protecting his own. Judge Cullen, visibly unimpressed, cut the moment short. With a few pointed questions he exposed the conflict, then firmly barred Gleason from taking part.

Freed of the Gleason’s looming shadow, the grand jury pressed forward, training its attention squarely on Burke and the charges against him. Outside, however, the drama lingered. Citizens buzzed over the showdown, left to ask themselves an unsettling question: just how far did Gleason’s influence reach; how much deeper did his hand run into the machinery of justice?

Court Rulings and Civic Indictments

The Supreme Court, before Justice Bartlett, ordered corrections to the election returns in eleven districts where Sanford’s name had been misspelled. Gleason’s counsel argued that every “creative” spelling created a different candidate; armed with legal precedent, the court disagreed and directed the ballots to be counted for Sanford.

Meanwhile, the grand jury castigated City Hall over the dismal condition of Long Island City’s schools; the condition of some were described more like “makeshift warehouse” than schoolhouse, with classes held in old factories and church basements. Gleason blamed political enemies for blocking improvements, but the report read like a blueprint for disaster.

The “Charity” Gambit

With both Gleason and Sanford publicly claiming victory, Gleason wrote Sanford on December 28, 1892, proposing a “peaceful and charitable” truce: he would continue performing the duties of mayor until the courts decided, while the mayoral salary would be deposited in Queens County Bank as relief for the poor and victims of a recent dynamite explosion whike blasting the underground tunnel that would eventually connect the F train from Manhattan to Queens.

Rumors flew that Sanford would try to seize City Hall by force on January 2, 1893. He quickly dismissed the talk, urging calm and respect for the courts and the city’s reputation: “He that ruleth himself is greater than he that ruleth a city.” He pledged to let the legal process run its course.

Judge Bartlett

Bartlett Allows Gleason to Intervene

Justice Bartlett granted Gleason the right to intervene in Sanford’s action for the mayoralty, putting both claims squarely before the court, a process that dragged on for months into the new year.

Election Returns Delivered

Complying with Bartlett’s order, Assistant City Clerk Hayes set out with the disputed returns in hand, the weight of the election quite literally bundled under his arm. When he delivered them to the inspectors of election, the crowded room hushed; this was no mere formality, but a decisive step that pushed the bitter contest out of the shadows of backroom maneuvering and into the stark light of legal review. Every eye followed Hayes, as though the fate of the mayoralty itself were riding on that single handoff.

Aldermen Oust the Clerk and Back Sanford

At a special meeting in January 1893, the anti‑Gleason Board of Aldermen finally struck back. Declaring Thomas Burke guilty of dereliction of duty, they voted to remove him and installed ex‑Sheriff Matthew J. Goldner as the new city clerk. But the transition was anything but orderly. Assistant Clerk Hayes flatly refused to surrender the office, and when the all‑important mayoral seal suddenly vanished without explanation, once again, the scandal deepened. Undeterred, the board authorized Goldner to set up a rival clerk’s office elsewhere in the city and approved the creation of a duplicate seal, since the original was formally reported stolen.

Sanford Acts

On January 10, 1893, Horatio S. Sanford was publically sworn into office by city clerk, Edward J Knauer, an Advance Lodge Brother, and declared himself mayor of Long Island City, organized a new administration, and directly challenged Gleason’s control of City Hall.

Proclamation, Recognition, and Appointments

Sanford issued his proclamation with military‑style pomp, the air thick with drums, a banner, and the cheers of an eager crowd. Standing before the assembly, he invoked the November election and his hard‑won 136‑vote plurality as proof of his rightful claim. Clerk Burke’s tampered returns had, for a time, carried Gleason’s name, but the truth could no longer be buried. One by one, legal corrections stripped away the fraud until the Board of Aldermen, bowing to both the evidence and the clamor of the public, allowed Sanford to take his seat at last as the lawful mayor. And so Sandford read his proclamation aloud.

Sanford announced key appointments:

• Corporation Counsel: William F. Stewart

• Private Secretary: George R. Crowly

• Police Commissioners: Patrick J. Daley, Jurgen Rathjen, and James Ingram, Brother of the Lodge.

Copies of the proclamation were swiftly posted across City Hall and pressed into the hands of the boisterous crowd, the ink barely dry as word of Sanford’s victory rippled outward through the city. Cheers rose as messengers carried the notices into the streets, and within hours the announcement was hnded out from Ravenswood to Hunter’s Point. Standing before his supporters, Sanford pledged “a clean and honest administration,” his voice cutting through the din as he called on the people themselves to quell their rage and allow the rule of law to handle Gleason in its due course.

Ongoing Disputes: A City with Two Mayors

Even after the aldermen formally recognized Horatio S. Sanford, Patrick J. Gleason stubbornly clung to the mayor’s office, maintaining his own shadow “administration” and keeping a loyal police detail stationed at City Hall. The halls of government became a stage for dueling claims, with most officials shifting allegiance to Sanford while a handful of die‑hards remained by Gleason’s side. Armed with legal sanction, Sanford pressed on; conducting official business under a freshly minted mayoral seal. Gleason’s loyalists dug in, but their cause faltered when the city treasurer refused to honor Gleason’s authority or issue salaries on his orders, leaving the “Boss’s” administration little more than a hollow performance.

Missing Records and a Grand Jury

As the standoff wore on, the drama only deepened. A grand jury convened to probe the disappearance of city records and to scrutinize the actions of former City Clerk Thomas P. Burke; the very man who had issued the contested election certificate in Gleason’s favor. Whispers spread through the city that Burke had vanished with crucial ledgers and the old mayoral seal, to intentionally impede the mayoral transition: a rumor that lent the power struggle an almost cloak‑and‑dagger quality

A Quiet Trip to Poughkeepsie

Amid the chaos, and as critics railed that City Hall was churning out shady contracts in its final days, Gleason took a desperate gamble. On the cold morning of January 24, 1893, his attorneys slipped north to Poughkeepsie, where, behind closed doors, they pleaded with Justice Barnard for an injunction to stop Sanford from taking office: a legal ambush obviously intended to keep Gleason’s fading power alive.

Legal Endgame and the Surrender of City Hall

Undeterred by each setback, Gleason’s lawyers pressed on, launching quo warranto proceedings in a last attempt to challenge Sanford’s claim to the mayoralty. The litigation dragged into the spring, keeping the city suspended in uncertainty while two governments seemed to hover uneasily over City Hall. At last, in early April 1893, Gleason had no choice but to yield. Hehanded over the records and finally vacated the mayor’s office. Yet the victory came with a sobering revelation. Behind the bluster and brawls, the true legacy of machine rule was plain to see: empty coffers, tangled contracts, and a civic fabric frayed by years of corruption. Sanford now held the title, but he inherited a city already scarred.

Seal of Long Island City

Sanford’s Time in Office

When Sanford at last became the sole mayor, Long Island City was effectively insolvent; its finances hobbled by patronage, disputed contracts, and accumulated arrears.

Barred from Collecting Taxes

Sanford’s first days in office brought not celebration but crisis. A crucial tax levy, meant to stabilize the city’s tottering finances, was struck down on a technicality, leaving him with an empty treasury and no lawful way to pay the bills. Grimly, he notified city employees and creditors that payments could not be made. Weeks turned into months as teachers, police, firefighters, contractors, and laborers all went without their wages, frustration mounting with every payday that came and went.

The fault traced back not to Sanford’s inexperience but to the chaotic handoff of power. Procedural missteps, missing signatures, and half‑finished business by the outgoing Board of Assessors had left the levy deliberately exposed to legal attack. And with the city clerk vanished into scandal, the mechanism to fix those flaws had collapsed altogether; setting the stage for a financial paralysis that crippled the new administration right from the start.

Empty Coffers

Beyond the levy fiasco, Sanford inherited an overdrawn city: heavy short‑term warrants issued under Gleason far beyond the coming tax receipts; costly, contested utility deals (notably the Woodside water supply) with large unpaid bills; an inflated payroll; arrears to vendors and employees; and mounting judgments and back‑pay claims from the Gleason-Sanford struggle. Local banks balked at extending more credit.

The infamous national financial panic erupted in May 1893, when U.S. gold reserves sank to the bare legal minimum and local jittery banks slammed the brakes on extending credit to the Mayors office. Even pillars of the community felt the tremors. The panic pushed James Otis, another stalwart of Advance Lodge, back into national politics, winning a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and serving from 1895 to 1897. In Washington, he joined colleagues in championing measures to shore up the gold reserve and raise tariff rates, part of a desperate bid to restore confidence.

Yet closer to home, Long Island City reeled. The panic struck with such force that the Advance Lodge itself barely survived. Its minutes from those years read like a chronicle of sacrifice and hardship; members sacrificing their own incomes, pooling resources, and channeling what they had left into relief efforts for neighbors. So relentless was the strain that, for a time, it seemed the Lodge might collapse under the weight of its own generosity.

Getting the Money Flowing Again

Sanford’s administration moved quickly to get the city back on its feet. They pushed for special legislation to create a new Board of Assessors, giving it the power to review and approve tax rolls so that much-needed revenue could start flowing again. Restoring those collections was critical; not just to keep city services running, but also to make sure workers were paid.

Amid the swirl of Gleason’s election fraud in the year before the vote, Theron H. Burden, a tax inspector and fellow Lodge Brother, suddenly found himself forced from office. The push wasn’t about his performance; by all accounts, he had carried out his duties capably. This was politics, pure and simple. Burden had dared to run for Sheriff on the Jeffersonian ticket, and though he lost, the campaign left behind raw grudges. Those resentments made him target for political retaliation, a casualty not of failure but of spite.

Burden didn’t give up on politics, though. An 1896 entry in the Steinway Diary records that he tried again that same year, running for the Improvement Commission; Gleason’s re-election kept him from succeeding. Even so, Burden remained active in public life, and in the early 1900s he took on a different kind of fight: helping to keep Tammany Hall’s well-known corruption from taking root in Queens.

The Centennial Hotel Scandal

On the eve of Sanford’s tenure, Gleason’s Board of Health pushed through a curious deal: leasing the Centennial Hotel for a staggering $3,000 a year—many times its worth—supposedly as a quarantine house for a rumored epidemic. Sanford refused to play along. He flatly denied payment for what he saw as a sham rent, demanding accountability in a city starved of it.

A Mayor Who Refused a Raise

One of Sanford’s first acts was to decline a legislated salary increase (from $2,000 to $2,500) arguing he’d been elected at the lower pay. He even pledged to return any excess if compelled to accept it. The gesture, modest but memorable, set an ethical tone for his administration.

What followed pulled back the curtain on Gleason’s scheme. In court, city attorneys laid out the truth: the mayor himself secretly owned the hotel, had orchestrated the deal for personal profit, and never so much as used the building for quarantine. Years later, Justice William J. Gaynor would not mince words, calling the contract a “barefaced fraud on Long Island City” and noting the property’s fair rental value was barely $400 to $500.

Sanford’s stand marked a turning point. By refusing to bankroll Gleason’s grift, he drew a clear line in the sand: public office, he insisted, was meant to serve the city, not function as a cash register for those in power.

Cleaning Up the Schools

As part of his reform initiative that swept through the police, fire and other civic departments, Sanford installed a new board of school commissioners and backed Superintendent Sheldon J. Pardee in an exhaustive review of teacher qualifications. Of 127 teachers, 28 lacked proper licenses; only 21 of those even held high‑school diplomas. The board suspended unlicensed teachers pending review, reassigned staff, replaced several principals, and condemned unsanitary “schoolhouses” that were little more than basements and factory rooms tied to Gleason’s allies.

Not long afterward, School Commissioner Daniel J. Kennedy stirred controversy by attempting to install his unlicensed brother as a school engineer. Sanford seized on the scandal, calling for Kennedy’s resignation and striking another blow against the entrenched machine politics of the city. The appointment was not merely nepotism; Kennedy’s brother had recently lost a series of lucrative city improvement contracts, contracts he had been paid for but had consistently failed to honor. His repeated defaults had landed him in a protracted legal battle with another Lodge member, Earnest Ankener, of the Long Island City First Ward Improvement Office.

Julius Arthur Von Hunerbein

The New General Improvement Commission

To shift from short-term crisis response to long-term planning, Sanford proposed creating a Board of Long Island City General Improvement to centralize oversight of major projects. The board brought together the Public Works Commissioner, two at-large aldermen, and two gubernatorial appointees. It was authorized to issue up to $1.5 million in bonds, signaling a move away from patronage-driven decisions toward accountable, systematic infrastructure planning.

Lodge Brothers Peter Van Alst and Robert Graham served as commission chairs. The General Improvement Commission also appointed a new surveyor and engineer, Julius Von Hunerbein, himself a Brother of the Lodge. His 1900 funeral was among the largest in the city’s history, reflecting the deep respect he commanded. Von Hunerbein was widely regarded as both a highly skilled surveyor and engineer, celebrated for expanding utilities, improving roads, and actively contributing to municipal politics. Although Mayor Gleason dismissed him after regaining office, the courts promptly reinstated Von Hunerbein, underscoring his stature and public support.

Press and the Libel Row

The reform fight played out in the press as well. In late December 1894, Edward Bell, editor of the Weekly Flag, was arrested on criminal‑libel charges after publishing a letter accusing Sanford and Commissioner Henry W. Sharkey of misconduct. Bell (also subject to militia discipline) was even summoned to a court‑martial. The episode captured the era’s combustible mix of politics, press, and personality.

Public Mobile Library in Jamaica Queens

Long Island City Public Library

A Public Library Takes Root

Years earlier, book lover and lodge brother Winthrop Turney, along with Dr. Walter G. Frey and George E. Clay, set the effort in motion. In 1896, Mayor Horatio Sanford helped launch what became Queen’s Public Library by allocating $3,000 in city funds to charter and open the Long Island City Public Library. After consolidation, that seed grew into one of the nation’s largest public library systems. Queen’s Public Library had publicly credited Sanford’s role, including it in its coverage of the library’s 125th anniversary on March 19, 2021.

Westward, to Oregon

After leaving office, Sanford looked westward for his next chapter. Announcing plans to join forces with M. J. Goldner in managing a promising gold mine in Ashland, Oregon, he traded civic halls for the prospect of frontier fortune. Within months the venture pulled him in completely, and he made the relocation permanent. Soon after, his family packed up the Ravenswood homestead and followed him across the continent, leaving behind the familiar rhythms of Queens for a bold new life in the shadow of the Siskiyous.

Rainey Park in Queens, New York.

Rainey Park and the Sanford Homestead

Years later, the city restored the historic Sanford house, as it was once home to Dr. T. W. Sanford, Horatio’s well known father, as part of expanding Rainey Park along the East River. With public investment, the site became a small museum piece of local heritage and a riverfront amenity, knitting civic memory to a renewed public space.

Sanford’s Leadership and Legacy

Sanford governed in a gale. He inherited empty coffers, a paralyzed tax levy, contested contracts, and a city divided by machine politics. His response was principled and practical: defend ballot integrity, reject self‑dealing (Centennial Hotel), refuse a personal pay bump, professionalize schools, centralize infrastructure planning, and seed enduring public goods like the library. Many of his reforms were less theatrical than Gleason’s public works, but they reset norms: merit over favoritism, lawful process over improvisation, and long‑term planning over short‑term gain.

Although Gleason briefly clawed his way back into office, it was Sanford’s imprint that endured, etched not in stone but in standards. Where the old boss thrived on bluster, Sanford insisted on order, process, and transparency: principles that drew Long Island City toward the governance Greater New York would soon demand.

He left no statue to tower in a square, no monument to gather pigeons and dust. What he left was more enduring: a library that opened minds, civic departments rebuilt on professional footing, and a new expectation whispered through the corridors of City Hall: that public money must serve the people first.

Gleason Aftermath and the End of the City

With Sanford gone from politics, and soon gone from the state, reformers looked elsewhere for a standard‑bearer. They rallied behind a new Citizens’ candidate, but the old machine proved resilient. In 1896, Gleason stormed back into office, bristling with defiance. He battled utilities and railroads, railed loudly against the looming consolidation, and even threw his weight behind lawsuits from former appointees ousted during Sanford’s reforms, demanding reinstatement and back pay.

But the tide of history was bigger than the “Boss” of Long Island City. On January 1, 1898, Greater New York was declared, and the independent government of Long Island City vanished overnight. Gleason’s mayoralty ended not with an election defeat, but with the stroke of consolidation. And his fiefdom dissolved into the vast machinery of the new metropolis.

Gleason’s Final Days

It is well documented that after consolidation, Patrick J. Gleason wandered the shifting landscape of Greater New York like a relic out of place. The new metropolis no longer bowed to the will of one man, and Tammany, ever pragmatic, saw him as a tool to be used, not a partner to be elevated. Without his old fiefdom in Long Island City, the Boss had no ground on which to stand. Slowly, his influence drained away, leaving behind only the echoes of his bluster.

He died in 1901, the ever loyal Burke was by his side. Calvary Cemetery received him quietly, a modest grave for a man who had once swaggered through City Hall with a police detail at his back. In a final irony, even his most sympatheric obituaries, cast him not as a statesman but as a “picturesque” figure of a bygone age. Once the master of a city, Gleason was now remembered as an artifact: colorful, even notorious, but ultimately isolated, his voice silenced while the metropolis he had fought against roared past him into the new century.

Conclusion: What Sanford Changed

Sanford’s mayoralty was brief, embattled, and consequential. He brought daylight to contracts, discipline to finances, professionalism to schools, and a plan to modernize city works. He planted a civic institution (the Queens public library) that still serves millions. In a city famous for spectacle, he made integrity the headline. What is put down here is only a very brief account of his acts in office.

It Is The Man That Makes the Mason, Not The Mason That Makes The Man

Sanford’s record of public service, fiscal prudence, and devotion to learning revealed a character already steeped in Masonic virtues long before he ever knocked at the Lodge door. His initiation in November 1893, nearly two years after his mayoral campaign, was not a beginning so much as a recognition, a formal seal on principles he had already lived.

He was not alone. James Ingram’s admission in September 1893 and Winthrop Turney’s in October 1894 marked the arrival of a small cohort drawn to the Craft not for ornament or prestige but for its deeper purpose: service, accountability, and enlightenment. These were qualities woven into their character long before an apron was tied at their waist.

Their example bore out an old maxim: Masonry does not manufacture integrity, it shelters it. The Lodge gave their convictions a home, their virtue a fellowship, and their lives a charge: a reminder that private honor must find public expression.

Sanford’s term in office exemplifies several virtues associated with Freemasonry:

• Brotherly love and community service: partnered with fellow lodge members and civic leaders to advance public good.

• Relief/charity: directed the public funds to a community asset, via the Long Island City Public Library.

• Enlightenment: championed access to knowledge and education through library building and cleaning up the school board system.

• Prudence: proposed a structured Board of City Improvement and responsible bond financing.

• Justice and accountability: sought to shift work from patronage to planned, transparent oversight.

• Fortitude: led through the post‑1893 crisis with institution‑building rather than short‑term fixes.

• Stewardship: focused on durable civic institutions that outlast any one administration.

• Leadership: convened diverse stakeholders to deliver major public works.