Brother Julius H. Striedinger: Quiet Craftsman, Lasting Impact

Article by Brete Murphy

In the story of Astoria, Queens, a tale often told in bustling commerce and crowded waterfronts, one name moves quietly but surely behind the scenes: Brother Julius H. Striedinger.

Raised to the sublime degree of Master Mason in Advance Lodge No. 635 on December 1, 1874, Striedinger did not arrive to our fraternity with noise or accolades. Instead, he brought the engineer’s gifts of diligence, precision, and devotion to the common good; qualities that shaped both his professional legacy and his enduring standing among brothers and peers.

Engineering Astoria’s Future: A Legacy of Safety and Commerce

Striedinger’s mastery was most clearly seen not in grand public gestures but in the subtleties of method. As a civil engineer, and for a time as assistant engineer to General John Newton, within the War Department’s ambitious river and harbor improvement programs, his work became foundational to 19th-century American infrastructure.

Although we read earlier about Brother Maillefert’s innovative blasting work during the initial phases of the Hellgate river passage, it was ultimately determined sometime around 1856, that improved methods were needed for the final phases of this endeavor. It was Brother Striedinger’s estimates, surveys, and progress reports that gave substance to ideas, to finally transform the treacherous East River into predictable life-lines.

One record credits him for designing a channel dredged 200 feet wide and 4,700 feet long to ensure safe passage, evidence of labor that, repeated across the region, made coastal commerce safer and New York’s prosperity possible. Another report thanks him for his quiet mastery of information; compiling, organizing, and clarifying the great volume of data on which reliable navigation depended.

Day by day, Striedinger’s routine blended hands-on fieldwork, testing depths, checking the operation of dredging equipment, ensuring datums were precise, with the rigor of the drafting table, where he translated the ever-shifting tides and muddy riverbanks into charts, tables, and specifications that brought public funding and private ingenuity together. This meticulous approach produced outsized benefits: tugs, barges, and coasters could run with less risk and fewer delays, and the waterfront communities of Astoria and Queens flourished on the steadier schedules and more reliable commerce his efforts made possible. Lower insurance premiums and reduced perils to life and property were his unheralded but invaluable gifts to the future.

Yet Striedinger’s skill was not confined to New York’s shores. His work is documented in various archives such as the Hagley Museum & Smithsonian; tracing a reputation that reached from government records to the practical knowledge of his trade. Here, he is emblematic of the humble engineer as builder of reliability; the unsung guardian whose technical insight and vigilance create the critical underpinnings of urban life.

For our lodge, his significance is profound and dual: as a brother, he embodied the Masonic virtues of order, improvement, and civic-mindedness; as an engineer at the forefront of New York’s harbor works, he helped give Astoria its lasting connection to the world. Brother Striedinger’s example teaches that Freemasonry’s purpose is not bounded by ritual or meeting room; it extends into the tumult and striving of civic progress, where a steady hand improves and steadies life for all.

Transforming Peril to Passage: The Hallett’s Point Revolution

Nowhere was Striedinger’s genius more apparent than at the infamous Hell Gate: a snarled, reef-strewn strait at the Astoria bend of the East River, dreaded for centuries by sailors.

Hallett’s Point was the chokehold, a hazard that wrecked vessels, inflated insurance costs, and threatened the region’s economic future. After unsuccessful attempts to line hazardous rocks with spring bumpers and a campaign of private blasting, it was Congress that authorized a systematic solution, entrusting the task to Gen. John Newton’s U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and, crucially, assistant engineer, Striedinger.

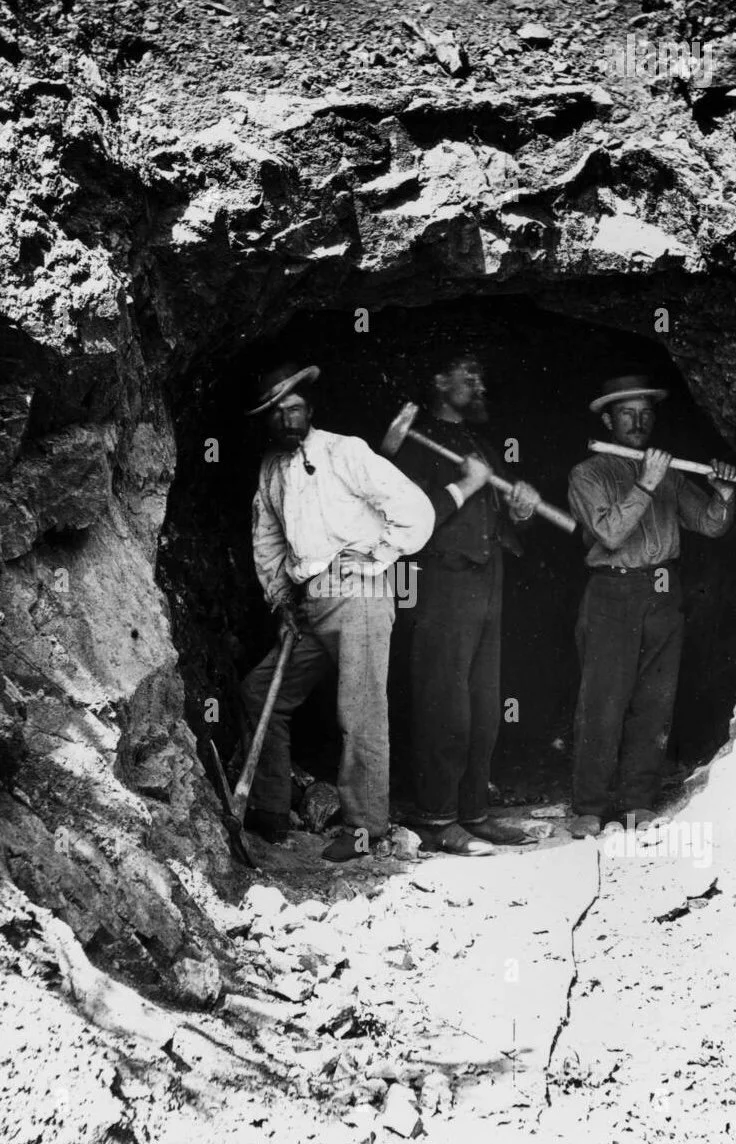

Rather than brave Hell Gate’s deadly currents, the project’s leaders pioneered bold new methods. They drove ten tunnels beneath the reef, creating a lattice of boreholes that enabled large-scale use of waterproof explosives. The real breakthrough was the charge plan: instead of piecemeal blasts, engineers fired a single, simultaneous electric detonation. The 1876 blast was both a spectacle and a milestone that proved the channel could be tamed.

Their ultimate target was Flood Rock, the stone island that turned tides into whirlpools and choked one of New York’s busiest passages. Over the next nine years, crews sank a deep central shaft, ran tunnels at multiple levels, and packed ceiling drill holes with about 283,000 pounds of explosives to widen and deepen the channel and calm its treacherous eddies.

On October 10, 1885, they flooded the mine to dampen sound and shock, then touched off what was then the largest man-made explosion until the atomic bomb. A geyser of water and rock shot 250 feet into the air as Flood Rock fractured and settled lower; remaining outcrops were finished with surface blasting. The shock was felt across the city and as far as Princeton, New Jersey, while an estimated 200,000 people watched from shore and from commercial and private vessels. As piano maker William Steinway noted in his diary that morning, “we feel the Hell Gate explosion at Flood rock, at 11.30 A.M.”

Fun fact: Wards Island (south) and Randalls Island (north) are now joined by landfill; mainly rock and earth from the 1930s Triborough Bridge project and the regrading of Randall’s and Wards Islands. The former passage between them was called Little Hell Gate, and both are now officially part of borough of Manhattan.

Although Hallett’s Cove itself remained tidal and open, this work marked the beginning of incremental yet deliberate shoreline transformation. City authorities and private owners steadily extended the shoreline, building out piers and bulkheads. For Queens and all of New York, the results were swift and far-reaching: navigation became safer, shipping lanes widened, and economic growth accelerated as Queens became more closely connected to New York and New England.

These undertakings, including the deepening of the Newtown Creek inlet, the removal of various rock formations throughout Hell Gate, and the shoring of the coastline from Hunters Point up to College Point, alongside the soon-to-be-built Brooklyn Bridge, Brothe’s, Robert Graham and Thomas Rainey’s Queens Borough Bridge project, ushered in a transformative era for commerce along the Hudson. At the same time, Brother’s Ankener and Peter Van Alst, working in the Long island City Improvement Commission, steadily improved the infrastructure throughout the area. Together, these efforts reshaped the movement of goods between Manhattan, Brooklyn, and what would become Queens. Materials now traveled more easily up the East Coast to Connecticut and beyond, signaling the first signs of New York’s heading toward a unified five-borough city and solidifying the region as a critical hub during the nation’s industrial advance.

Responsibility for these sweeping changes during the final Hell Gate phase fell jointly to federal engineers and to the field expertise of men like Striedinger, whose methods became manifest in the infrastructure that would support a rapidly growing city.

For Astoria’s Masonic community, these advances were not only feats of engineering, but living examples of the fraternity’s belief that society could be improved through reason, patience, and planning.

Exporting American Ingenuity: Striedinger’s Innovations on the World Stage

Julius H. Striedinger’s influence did not end on American shores. In 1878, he and his associate Doerflinger presented their Model of Blasting Apparatus at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, which was a world’s fair defined by its celebration of technological and social progress.

Their model, listed formally as “Model of Blasting Apparatus, as used for the great explosion at "Hell Gate," New York.”, bore witness to American innovation, demonstrating the synchronization of massive charges, an approach that civilized danger and made large-scale improvements possible without endangering life or property.

This was the same apparatus that had tamed Hell Gate. In the same decade, Striedinger secured a U.S. patent for an “Improved Cartridge for Destroying Buildings,” a tool to help fire departments create firebreaks and protect crowded cities from catastrophic blazes; a response to the tragedies of Chicago and Boston. In both cases, his inventions served not only to conquer obstacles but to protect life and commerce: precision harnessed for public safety.

At the Paris exposition, set amid electric lights and the gaze of international dignitaries, Striedinger’s work became a symbol of the age: bold yet measured, inventive yet humane, contributing to the circuits of adoption and exchange that linked continents and capitals. His methods were amplified by the American Society of Civil Engineers, his inventions marked by catalogue entries and referenced in professional journals. In presenting his work, Striedinger gained the respect of peers and the attention of officials across Europe: his ideas diffusing into policy and practice around the globe.

Legacy of Reliability: Brotherhood, Civic Duty, and Progress

Brother Julius H. Striedinger stands as a foundational figure not only for Astoria and Advance Lodge No. 635, but for an entire era; an engineer whose careful works safeguarded lives and shaped the flow of commerce, and an inventor who carried American ingenuity to the heart of Europe’s industrial conversation.

He reminds us that the values of our lodge (order, discipline, improvement) find their highest expression in service to the public good. His legacy is written not only in records and patents but in the steady progress of a city, the security of its people, and the undimmed promise of its future.