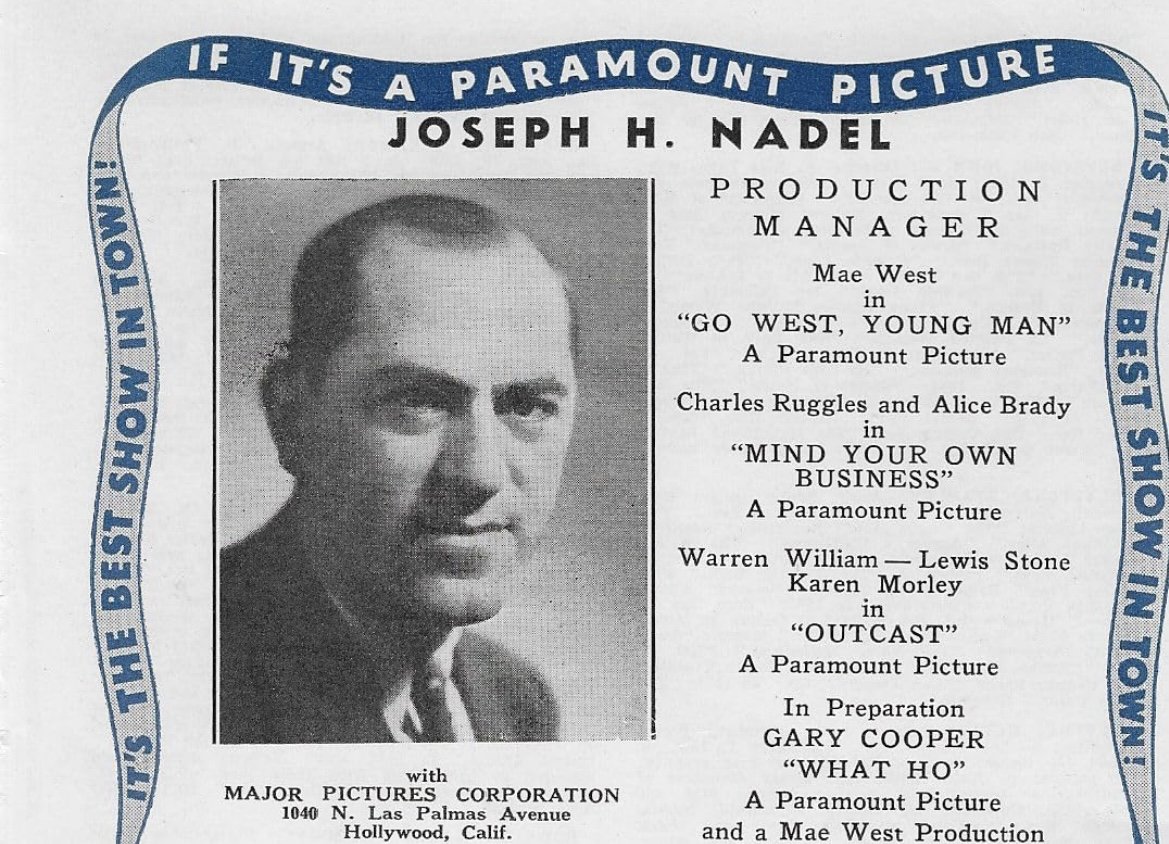

Brother Joseph H. Nadel, Mason and Film

From New York Streets to Hollywood Lights

Joseph H. Nadel’s story begins, as so many New York stories do, on a hot summer day in the city, long before the bright lights of Hollywood ever found him. Born on June 2, 1892, in New York City, he arrived in a world of pushcarts, elevated trains, and crowded tenements, where the streets themselves seemed to hum with possibility.

Long before his name rolled by in studio memos or appeared in the tiny credits of movie ads, he was simply Joe from New York: a boy who would grow into the kind of man people remembered as “well organized and detail oriented,” the quiet backbone you only truly notice when it’s gone.

From Streetcorners to Studio Gates

By the time the motion‑picture business began its awkward, flickering adolescence, Joe Nadel was already finding his way into the “screen trade.” Not as a star, and not yet as a name above the line, but in the trenches as a property man; the fellow who made sure the things an actor touched actually showed up on set at the right time, in the right place.

In 1925, tucked into the inside pages of the Los Angeles Evening Post‑Record, there’s a tiny entry, just a few lines among a flurry of studio gossip:

“Joseph H. Nadel and Hugh Bennett have organized the Nadel–Bennett Productions and plan to make a series of 2‑reel subjects entitled ‘Gems From Life.’ The title of the first is ‘Affection,’ which goes into production immediately.”

Two‑reelers were the workhorses of the era: short films that filled out a program, sometimes comic, sometimes dramatic, always made lean and fast. The announcement reads like a small thing, the sort of item that comes and goes every week in trade columns.

But for a property man turned production man, it meant something bigger: Joe was stepping out front, trusting his instincts, and taking his place as a producer.

The Los Angeles Times would later write that he entered the industry as a property man “35 years” before his death, putting his start around the mid‑1910s, when films were still learning to talk and studios were still learning to dream. From there, he worked his way steadily upward: assistant director on silent and early sound productions, production manager on comedies and dramas, then associate producer on the kind of pictures that would stick in the collective memory.

It wasn’t glamorous work, not in the way magazines liked to photograph glamour. It meant schedules and budgets, problem‑solving and diplomacy, the endless business of saying “no” softly and “yes” only when the numbers agreed. But in the factory that was the Hollywood studio system, men like Joseph H. Nadel kept the assembly lines moving and the cameras turning.

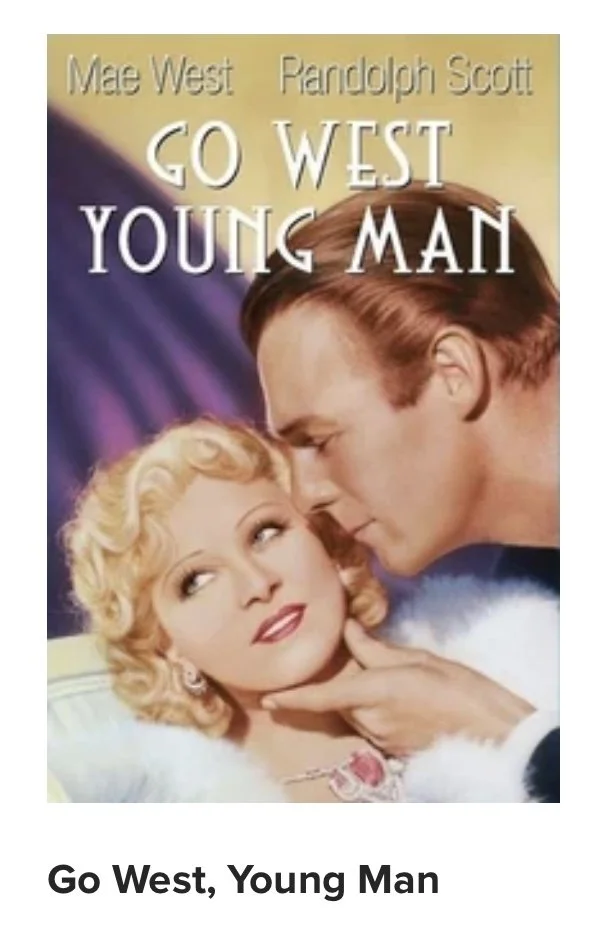

Mae West, Wisecracks, and Controlled Chaos

By the 1930s, Joe had become exactly the kind of man studios liked to trust with complicated productions. A Mae West blog, written decades later, remembers him plainly: he was the production manager on two of her films, Go West Young Man (1936) and Every Day’s a Holiday (1937). If Mae West was all curves, quips, and controversy, someone had to stand just out of frame with a call sheet, a stopwatch, and a pencil. That someone was Joe.

The blog notes that “like Mae, he was a native New Yorker,” and you can almost imagine the shorthand between them: that shared city rhythm, that dry, knowing humor. West drew the spotlight; Joe wrangled the circus behind it. On a set full of egos, he was the one who quietly made sure the film that existed in memos and meetings became a finished reel in a can.

To stand behind Mae West at the height of her powers was no small assignment. Her films weren’t just comedies; they were cultural events, battlegrounds of innuendo and censorship and star power. The posters shouted her name in letters taller than a man.

In those years, Joe’s title, production manager, meant he straddled two worlds: the creative chaos of the set and the unforgiving logic of the front office. He knew where the money went, how long the day could stretch, and which corner could be cut without the picture falling apart. Those who worked with him remembered a man who could keep a show on the rails without raising his voice.

Building a Career, One Credit at a Time

Hollywood remembers its stars with marquee lights and photo spreads; it remembers its producers and production managers with lines of agate type in the trades. Scan that fine print and a story emerges. Under his own name and sometimes as “Joe Nadel,” he turns up again and again.

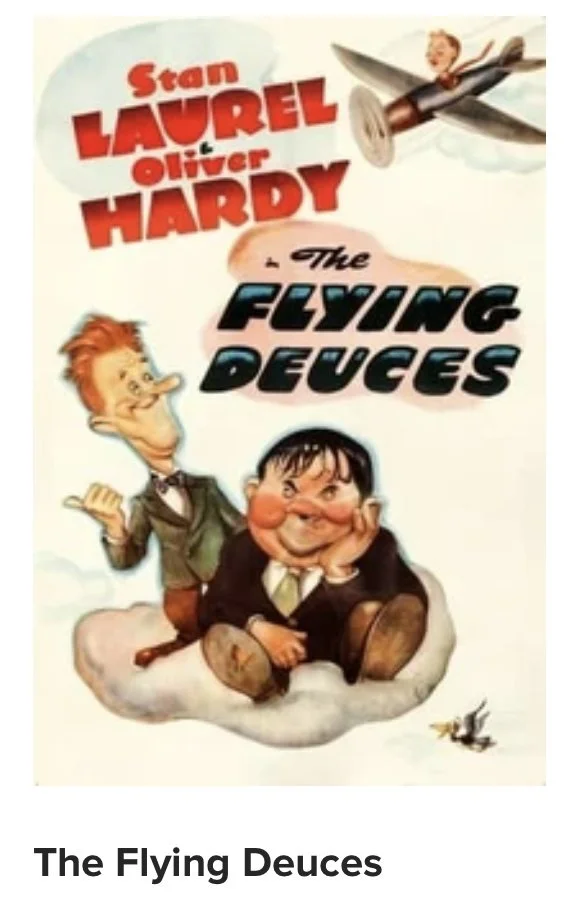

He handled production on films like The Flying Deuces (1939), the Laurel and Hardy comedy that still loops in late‑night retrospectives, and Beyond Tomorrow (1940), a seasonal ghost story that found new life on television.

He managed the logistics on And Then There Were None (1945), a nimble adaptation of Agatha Christie’s mystery, and kept the massive wartime ensemble of A Walk in the Sun (1945) marching in step. When the Western Abilene Town (1946) needed that dusty, lived‑in authenticity, Joe was there too, making sure the horses, the weather, and the budget all cooperated just enough.

By the late 1940s, his credit line had edged up the ladder. He was associate producer on a string of pictures that quietly endured:

• My Dear Secretary (1948), a light comedy about writers, romance, and deadlines

• The Big Wheel (1949), a racing drama with Mickey Rooney

• Impact (1949), a noir‑tinged thriller

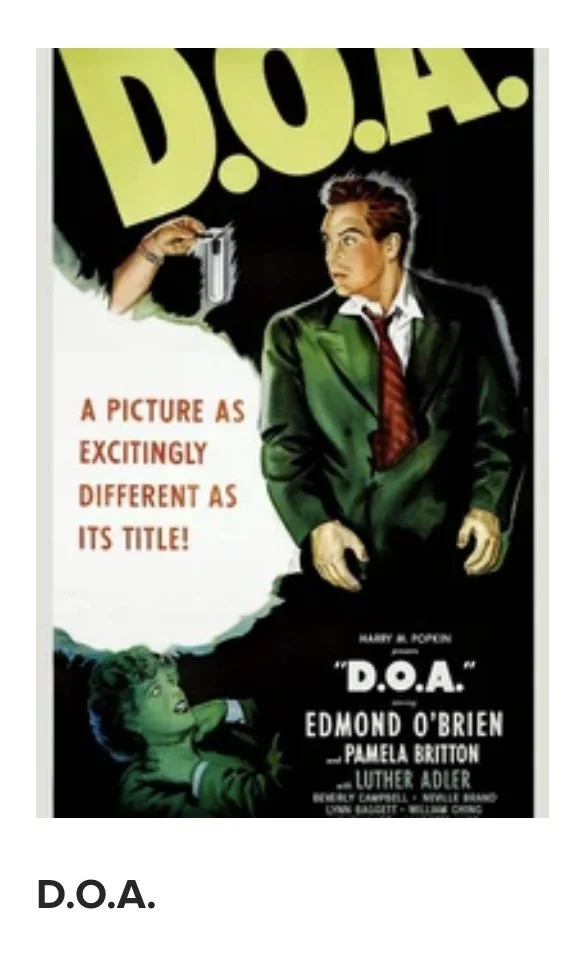

• And then D.O.A. (1949), the dark little masterpiece that would outlive nearly everyone who worked on it

In D.O.A., a man learns he has been fatally poisoned and races against time to solve his own murder. It’s baroquely fatalistic, both pulpy and sophisticated, and it owes its life to the sort of behind‑the‑scenes craftsmanship Joe embodied: tight shooting schedules, efficient sets, and the ability to squeeze suspense from modest resources.

When the Mae West blog says he worked his way up “from production management during the 1930s to producer and associate producer of full‑length features from 1934–1950,” it’s describing exactly this trajectory: the quiet, steady climb of a man who knew how a film was built from the ground up.

Hollywood at Home: 307 North Citrus Avenue

By the mid‑1940s, the Nadel family’s Hollywood address appears regularly in the society and news columns: 307 North Citrus Avenue.

It wasn’t a mansion in the hills or a legendary star’s palace. It was a solid address in a growing city, the kind of place where a working studio executive raised his family and tried to keep the studio drama at the studio and the home quiet.

In 1943, a charming notice ran in the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News:

“Expected home shortly from their honeymoon at Lake Arrowhead are Capt. Herbert Livingston Kehr of the Army Medical Corps and his bride, who was Miss Evelyn Nadel… The bride is the daughter of Joseph H. Nadel, production manager of the Samuel Bronston Pictures Corp., and Mrs. Nadel, and the family residence is at 307 Citrus Ave.”

This wasn’t just a credit in Variety. This was the way his work life crossed into his home life: “production manager of the Samuel Bronston Pictures Corp.” as part of his daughter’s wedding announcement. The Nadels would have read the morning Times, clipped notices like this, and stuck them in an envelope for relatives back in New York. The movies were how he made a living, how he put a daughter in a wedding dress and a son, Arthur, through his own path in life.

You can picture the house: a well‑kept home serving double duty as family anchor and industry outpost. Phones ringing in the hallway; call sheets and script pages on the dining table; Dorothy managing the quiet dignity of a home where a man is always halfway between dinner and the next picture.

Brother Joseph: Lodge, Charity, and Community

It’s easy to think of classic Hollywood figures as floating only in the rare air of studio lots and premieres. Joe’s life, as the paper trail shows, was grounded in something older and simpler: community.

In New York, years before his Hollywood address appeared in California columns, he was “Brother Joseph Nadel” of City Lodge No. 408. A lodge notice from the early 1950s, looking back in sorrow, contains a simple memorial line:

“In Memoriam

BROTHER JOSEPH NADEL

Raised June 20, 1921

Asleep November 20, 1950

May his soul rest in peace.”

Masonic lodges are for men who like structure, ritual, and mutual responsibility. It fits what we know of Joe from the film side: organized, detail‑oriented, a man who understood that grand designs rest on small, repeated acts done faithfully.

1946 Mt. Sanai, All Star Dinner Dance Charity Event

In Los Angeles, that instinct found an outlet in charity work. A 1946 notice in the Citizen News lists him as:

“Joseph H. Nadel, chairman of entertainment”

for a major benefit dinner‑dance supporting Mount Sinai Free Hospital and Clinic. The program roster was a who’s‑who: Jack Haley, the Andrews Sisters, Red Skelton, and more. Someone had to turn that list into an actual evening. Someone had to schedule the performers, coordinate with the band, arrange introductions, keep the tempo of the night moving and the donors happy.

That someone was Joe.

He was also, very simply, a brother.

When he died, a letter from a Paramount executive in Hollywood was sent to his brother Harry in New York, expressing shock at Joe’s sudden heart attack and enclosing Joe’s Variety obituary as a “fitting tribute to his many accomplishments.”

A Golden Age, Seen from the Side

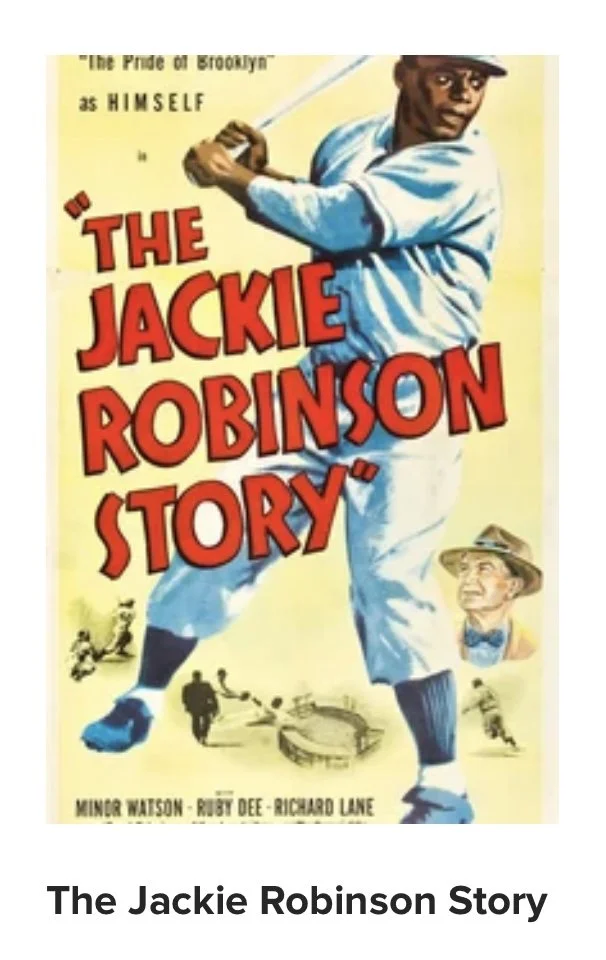

If you want to know what kind of films Joe gave his life to, look at the late 1940s and 1950. In those years, he served as associate producer on:

• Champagne for Caesar (1950), a witty satire about quiz‑show mania

• The Second Woman (1950), a moody drama

• The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), telling the real‑life struggle of the first Black player to break Major League Baseball’s modern color line

The Jackie Robinson Story, reviewed in the Valley Times and the Los Angeles Times that summer, was praised as a simple, direct account of a young athlete’s “fight for recognition,” anchored by Robinson’s own performance as himself. Critics singled out the film’s restraint, its focus on quiet perseverance and self‑control in the face of grotesque prejudice, and they named the key players behind the camera: Mort Briskin as producer and Joseph H. Nadel as his associate.

There is something fitting about Joe ending his career on that picture. The movie tells the story of a man who stays composed under the worst kind of abuse, who keeps showing up, keeps doing his job, and eventually wins over the very crowds that once hurled insults at him. It is, in a way, the story of every working professional in Hollywood whose labor was essential but whose name never became a household word. Joe understood athletes, performers, and teams; he knew the invisible weight of expectation, the strength of quiet discipline.

In those same years, he was announced as part of a team planning to produce Francis, David Stern’s comic novel about a talking mule, alongside Robert Stillman and Arthur Lubin. The project was noted in the studio briefs and gossip columns: another production, another schedule, another puzzle for Joe to solve.

He and his team did produce the book and were in works to produce the film. If not for his untimely death, his name may have been on the credits of that series as well.

Dorothy at His Side

At Hollywood Forever Cemetery, in the Beth Olam section, the stone is shared. The cemetery listing reads simply: “Nadel, Dorothy, b. 1893, d. 1959, s/w Joseph Nadel.” A Mae‑West‑era blog, looking back from the vantage point of 2011, adds a touch of warmth: Joseph was laid to rest in Hollywood Forever Cemetery, and “his loving wife Dorothy Nadel 1893–1959 was buried at his side nine years later.”

The public record is quiet about Dorothy’s early years. There are suggestions of a New York birth around 1893, and scattered facts that can be said with confidence are few: she married Joe, raised their children Evelyn and Arthur, moved across a continent as his career demanded, and made a home at 307 North Citrus Avenue. She endured the long hours and uncertainties of a film worker’s life, the late‑night calls, and the stretches when studio fortunes rose and fell with the box office.

When the Los Angeles Times printed Joe’s death notice, Dorothy is there in the first line, “beloved husband of Dorothy,” and again in the fuller obituary as the widow who survives him. Nine years later, she joined him in the same plot, their names carved together in stone; a reminder that behind every industry life is a partnership that rarely makes the papers.

A Final Fade‑Out

On November 20, 1950, at his home on North Citrus, Joseph H. Nadel died of a heart attack. The Evening Citizen News called him a “veteran production manager,” noting that he had worked in motion pictures for 35 years and that funeral services would be held at Hollywood Cemetery Chapel, followed by interment in Beth Olam. The Los Angeles Times echoed the details: age 57, long service to the industry, a man who had risen from property man to assistant director, production manager, and associate producer.

Back in New York, City Lodge No. 408 printed its brief memorial: “BROTHER JOSEPH NADEL Raised June 20, 1921 — Asleep November 20, 1950 May his soul rest in peace.” On the West Coast, colleagues clipped his Variety obituary, enclosed it in condolence letters, and tried to put into a few lines what it meant to lose the kind of man whose job, at its best, meant avoiding disasters no one would ever see.

Today, when his name appears online, it’s often in small fonts: a cast‑and‑crew listing on a database, a footnote in a blog about Mae West, a line in a local paper scanned into digital archives. Yet taken together, those fragments sketch a sturdy, unpretentious life: an American film‑industry professional whose career traced the arc of Hollywood’s golden age; a New Yorker who carried his city’s grit and humor into the studios of Los Angeles; a husband to Dorothy, a father to Arthur and Evelyn, a brother to Harry, Will, Edward, and Ann; a Mason, a committee chair, a man whose work “supported several enduring films” without ever demanding applause.

In the dark of a revival theater, when the credits for D.O.A., The Flying Deuces, And Then There Were None, or The Jackie Robinson Story start to scroll past, his name is easy to miss. But it’s there, quiet and steady (just like Joe) doing exactly what it always did: its job.