Brother Anthony “Speed” Hanzlik: Freemason, Aviation Pioneer, and Queens Sky king

Discovering a Masonic Aviation Pioneer

While poring over dusty lodge ledgers and faded member registers, a name flew me straight back to childhood: Brother Anthony “Speed” Hanzlik, who owned and managed Flushing Airport. Queens’ last private airport, closed in 1984 by Mayor Ed Koch due to chronic flooding, crashes, and competition from the rapidly expanding LaGuardia and JFK airports.

Researching Flushing Airport unlocked memories of a gritty Queens brimming with possibility, now echoed in its derelict relics. It traced industrial America’s arc from pre-WWI ingenuity to Cold War corporate dominance, where homegrown ventures yielded to polished giants.

Summer Skies Over Queens

The seasonal signs that let children of my age-group know summer was upon us, were plush trees, the sighting of an oriel, and kids pointing to the sky, exclaiming, “Look, the Red Baron.” The Rockaway beach of my youth had the scent of sea salt and coppertone, set to the constant soundtrack of a wooden rollercoaster cranking its way to the top, followed by the giddy passangers on their way down. Kids’ eyes often locked skyward as skywriters traced messages and banner planes hauled ads, from cold soda to the rare marriage proposals, and everyone’s face lit up at the sighting of the Goodyear blimp.

This aerial spectacle, powered by Hanzlik’s vision, defined Queens summers for decades. Social media still hums with nostalgic tales of the blimps moored at Flushing Airport and old gripes over the buzzing traffic from the Red Baron and the infamous Yellow Jacket flights.

Hanzlik’s introduction to flight

Back in the early 1800s, Queens neighborhoods like Hunter’s Point, Newtown, Astoria Village, and College Point caught the eye of big dreamers. People like Steven Halsey, William Steinway, and Conrad Popenhusen saw beyond the quiet shoreline communities to a shared vision of a booming center for industry and shipping.

Conrad Poppenhusen’s innovative use of vulcanization earned him an exclusive license from Charles Goodyear in 1852. Goodyear moved its Headquarters from Ohio to Queens, sparking College Point’s rise as a key rubber manufacturing center. By the 1910s, the Queens area had added bridges, tunnels, and enhanced freight ferries, and realized that industrial vision of this area. It became a vital hub for production and distribution during World War I. A growth continued for decades with ongoing improvements to factories, railroads, and boatyards.

Around 1916, the Wright brothers opened the Wright-Martin factory in Long Island City, Queens, turning the neighborhood into a humming outpost of American aviation. In the busy corridors of that plant, a young courier named Hanzlik earned the nickname “Speed” by racing critical messages through the shop floors and drafting rooms with relentless energy. During the 1910s, Long Island City stood at the forefront of flight innovation, drawing daredevils, engineers, and dreamers into its orbit.

Hanzlik quickly graduated from messenger to barnstormer, taking to the air alongside legends and life long friends, Eddie Rickenbacker and Jimmy Doolittle. He flew unlicensed in the largely unregulated skies over New York, where every stunt and test flight carried real risk. Between shows and record attempts, he strapped a camera into the cockpit and snapped dramatic images for all the major New York newspapers, threading his way through hazardous assignments with a cool precision that matched his nickname.

Queens: Sky-High Hub of the 1920s

It may be hard to imagine today, but during aviation’s experimental golden age in the 1920s, Queens buzzed with private and commercial airports dotting its landscape like stepping stones to the future.

Forgotten Fields:

• Holmes Airport in Jackson Heights served as a private hub for air shows and general aviation on 220 acres of undeveloped land, drawing crowds until competition from larger fields forced its closure by 1937.

• Glenn Curtiss Airport in Elmhurst, near the old North Beach amusement resort, opened in 1929 on 105 acres as a state-of-the-art facility with gravel runways, hangars for over 70 planes, and service for both landplanes and seaplanes; the city rebuilt it in 1939 as New York Municipal Airport-LaGuardia Field.

Flushing Airport: Masonic Beacon in Queens Skies

In 1927, Hanzlik transformed a Queens swamp into Speed’s Airport, which became Flushing Airport by 1936. A hub for biplanes, skywriting squads, and Goodyear blimps, it stood as a symbol of craftsmanship, innovation, and community amid New York’s evolving aviation scene. The airport also featured in films like [The Blaze of Noon][1] and The Spirit of Saint Louis, starring Jimmy Stewart.

[1]: In 1927, Hanzlik transformed a Queens swamp into Speed’s Airport, which became Flushing Airport by 1936. A hub for biplanes, skywriting squads, and Goodyear blimps, it stood as a symbol of craftsmanship, innovation, and community amid New York’s evolving aviation scene. The airport also featured in films like The Blaze of Noon and The Lindbergh Story, starring Jimmy Stewart.

Emergency Park Landings

In In 1935, Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a massive federal program that created millions of jobs and led to the construction of many municipal buildings and parks still enjoyed today. One memorable incident involved Anthony Hanzlik, who made headlines by forcing a halt to WPA work with an emergency landing in Prospect Park. He later also made an emergency landing in Roosevelt Park on the Lower East Side. Despite the causes he was noted more for his perfect and safe landings.

Speed Hanzlik: Queens’ Covert Gatekeeper to the Skies

The Clayton Knight Committee was a covert recruitment organization founded in 1940 by American World War I aviator Clayton Knight and Canadian ace Billy Bishop to enlist U.S. pilots and aircrew for the English air force during America’s pre-Pearl Harbor neutrality.

Formation and Operations

Knight, leveraging his aviation contacts and set up headquarters at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel with branches across major U.S. cities, funded by figures like Homer Smith despite violating U.S. neutrality laws. Recruiters used word-of-mouth, and discreet screening to channel nearly 7,000 Americans to Canada, bypassing border issues and State Department protests.

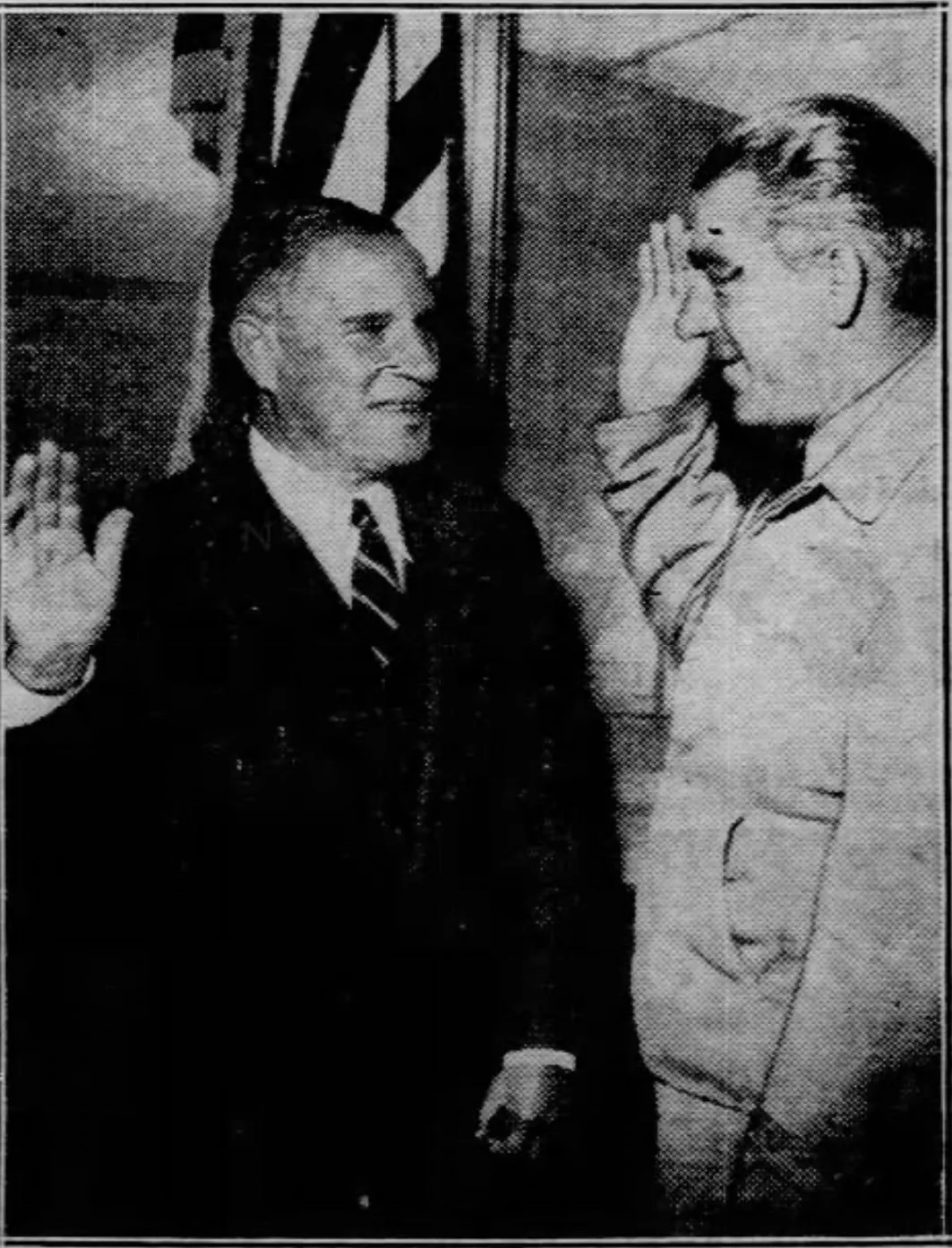

Anthony “Speed” Hanzlik was enlisted as New York’s tough-love examiner for the Committee in 1941, grilling pilots dreaming of RAF or RCAF glory. Sworn in as Queens Aviation Director by Borough President Br. George U. Harvey, he vetted only the elite (approximately one in five), rejecting any pilots needed stateside, and ensuring 300+ flight hours for Hurricane, Spitfire, and Blenheim duties. He funneled over 500 Yank fliers to Britain’s desperate skies, bridging isolationist America to the Blitz’s roar.

Patriot Pipeline in Pre-Pearl Harbor Days

Hanzlik’s role supercharged the Eagle Squadrons and ferry ops, shuttling bombers across the Atlantic with a stellar safety record, while recruits mastered multi-engine beasts without having to give up U.S. citizenship. This volunteer surge, greased Lend-Lease wheels, arming Allies as U.S. factories revved for war; Hanzlik’s tests at Flushing echoed his WPA-era foreman chats, now prepping aces for global dogfights.

Experimental Edge and Lasting Legend

Beyond exams, Hanzlik tested cutting-edge gear like dirigible mooring masts and novel airships at Jamaica Sea Airport (Now part of JFK Airport), blending his pioneer photography with military tweaks that foreshadowed WWII blimps scouting U-boats off New York. Revered as a steady hand from 1930s barnstorming to 1974’s passing, his work knit civilian wings to war machines, propelling America from neutral skies to superpower ascent.

Championing Women Pilots and the Ninety-Nines

Alongside him, his wife Wilhelmina, known as Willie, exemplified the progressivism and inclusiveness that Freemasons also value. A dedicated member and leader in the Ninety-Nines; a pioneering women pilots’ organization founded at Curtiss Field in 1929. Willie helped break barriers. Their joint journey through aviation history not only brought Queens new aerial horizons but cemented their legacy within communities pushing social advancement through flight.

The Ninety-Nines: Trailblazers of the Sky

Founded on November 2, 1929, still in existence today, the Ninety-Nines emerged from a hangar meeting of 26 licensed women pilots amid the roar of engines and toolbox tea service. Inspired by the 1929 Women’s Air Derby (dubbed the “Powder Puff Derby” by Will Rogers), the group aimed for mutual support, job opportunities, and a central hub for women aviators in a male-dominated era.

Iconic Members and Feats

Amelia Earhart served as first president in 1931, while Louise Thaden won the inaugural Air Derby and held key early roles. Jacqueline Cochran set speed records and led the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), Phoebe Omlie became the first woman federally licensed for transport flying, and Ruth Nichols pushed altitude and distance boundaries. Willie Hanzlik was treasurer in the 1950s.

Willie Hanzlik: Dedicated Force in Women’s Aviation

In 1953, Willie Hanzlik represented the Ninety-Nines at memorial services in New York for a fellow aviator, showcasing her commitment to honoring peers, while later attending FAI banquets and conventions, often flying in with colleagues. After her husband’s death in 1974 at age 71, tributes highlighted her enduring service spanning 26 years, including designing educational tools, along side fellow 99er Linda Rooker.

World’s Fair: Aviation’s Grand Stage

Hanzlik’s role expanded during the iconic 1964 New York World’s Fair held just minutes from Flushing Airport at Corona Park.

Heliport Pavillion

The fair featured a prominent Port Authority Heliport pavilion in the Transportation Zone (now Terrace on the Park) which hosted New York Airways helicopter shuttles to LaGuardia, JFK, and Manhattan, indirectly leveraging Flushing Airport’s proximity for regional rotorcraft traffic. Flushing’s runways handled overflow general aviation and promotional flights, reinforcing Queens’ aviation hub status during the event.

Hanzlik’s airfield buzzed with private planes ferrying visitors eager to explore the fair’s promises of future innovation. Notably, the airport hosted Goodyear blimp moorings in 1964 and 1965, offering breathtaking flights over pavilions, including the futuristic Port Authority Heliport Pavilion.

Goodyear Blimp Moorings

Two Goodyear blimps, Mayflower and Columbia, moored at Flushing Airport in 1964 and returned in 1965 specifically for World’s Fair promotion, offering flights over the fairgrounds and drawing crowds for landings visible from nearby Little League fields. Eyewitnesses, including a young Alan Gross who later became a blimp enthusiast, watched the airships tie down, sparking lifelong interests amid the fair’s spectacle.

Legacy of Brotherhood and Flight

Hanzlik’s life is more than a collection of flight hours; it is a testament to enduring values, self-discipline, service, and mutual support, that mirror Freemasonry’s principles. His stewardship of Flushing Airport through decades of urban expansion, economic shifts, and technological revolutions kept a slice of Queens grounded in its pioneering roots. Upon his passing in 1974, his devoted wife Willie carried the torch, continuing the family’s imprint on flying and community until the airport’s closure in the 1980s.

Flushing’s Echo in Queens History

Today, you can still see its swampy ruins And faded runway whispering of that lost glory, urging us to honor pioneers like Hanzlik who kept local skies soaring. Airships Unlimited lobbied in 2000 to reopen Flushing as a dedicated “blimp port,” citing its Goodyear history from the 1960s, though competing development plans stalled the idea. There are still pending proposals to take down the derelict hangers, dredge the land and build massive condominiums or rental complexes.

For us at AstoriaMasons.org, celebrating Brother Anthony “Speed” Hanzlik is an homage to New York’s rich Masonic and aviation heritage, a tribute to a man whose life bridged the earth and sky with both skill and heart.