A Judge Who Helped Elect Lincoln… and Once Tried Mark Twain

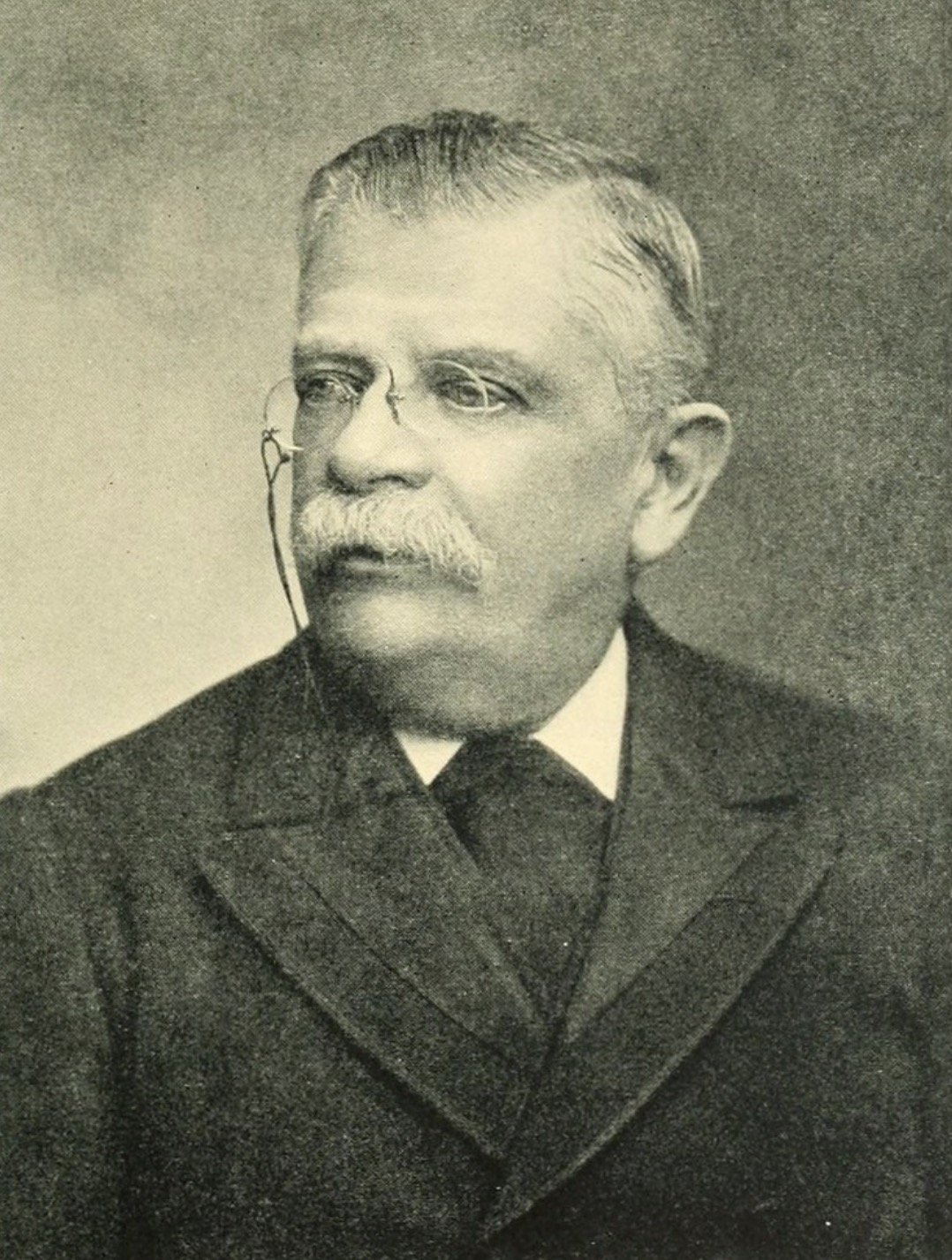

Bro Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer, City Lodge no. 408

The Remarkable Life of Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer

If you tried to pitch Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer as a character in a historical novel, most editors would send him back with a polite note that he was “unrealistic.”

Here was a German‑Jewish kid, born in slave‑holding Charleston, who moved to New York, became a fierce abolitionist, helped put Abraham Lincoln in the White House, turned down a federal judgeship from Lincoln himself, made legal history in everything from international extradition to theatrical copyright, rose to prominence in New York Freemasonry… and, for good measure, once presided over a mock trial of Mark Twain on the charge of being “the most unconscionable liar in the world.”

And that’s the short version.

For Freemasons, students of Lincoln, theater lovers, and anyone who appreciates a good courtroom story, Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer is one of those “how did I never hear of this guy?” figures.

Columbia University mid 1800’s

From Charleston to Columbia: A Southerner with Northern Principles

Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on March 17, 1836, to German‑Jewish immigrants Isaac Dittenhoefer and Babette Englehart. In 1840 the family resettled in New York City, where his father prospered as a merchant and gained a reputation for generous support of young strivers trying to get a foothold in America.

Young Abram proved to be the kind of student who makes everyone else in the class quietly resentful. At Columbia College he swept the Latin and Greek prizes year after year. Charles Anthon, the legendary classicist, reportedly called him the “ultima Thule” of his class; the farthest point of academic attainment, which is a very professorial way of saying “this kid is scary good.”

He graduated in 1855 (often cited as 1856 in contemporary accounts) with the highest honors, then took up the law in the New York firm of Benedict & Boardman. By 21 he’d been admitted to the bar; and by 22 he was already making enough political noise to be nominated for the City (then Marine) Court.

There was just one problem: he was a Republican. In 1850s New York City, that alone counted as an uphill legal argument.

Choosing Lincoln, Against His Father’s Wishes

You might expect a young Jewish lawyer from the South, with a successful merchant father, to gravitate toward the Democratic Party of the era. Abram’s father certainly did. But the son had other ideas.

What turned him? According to later accounts, Dittenhoefer was deeply impressed by an anti‑slavery speech he heard from fiery Republican Benjamin Wade, who denounced Confederate leader Judah P. Benjamin as an “Israelite with Egyptian principles”; a Jew, in other words, siding with the slave‑drivers rather than the slaves.

The line stuck. Dittenhoefer threw in his lot with the new Republican Party and never looked back, even over family objections.

By 1860, while still a very young attorney, he was already a valued campaign speaker; especially among German‑American voters. He soon became chairman of the German Republican Central Committee of New York, a post he held for twelve years. In an era when stump speaking was a blood sport, Dittenhoefer was a star: clear, witty, and relentless.

He didn’t just talk about Lincoln. He helped elect him.

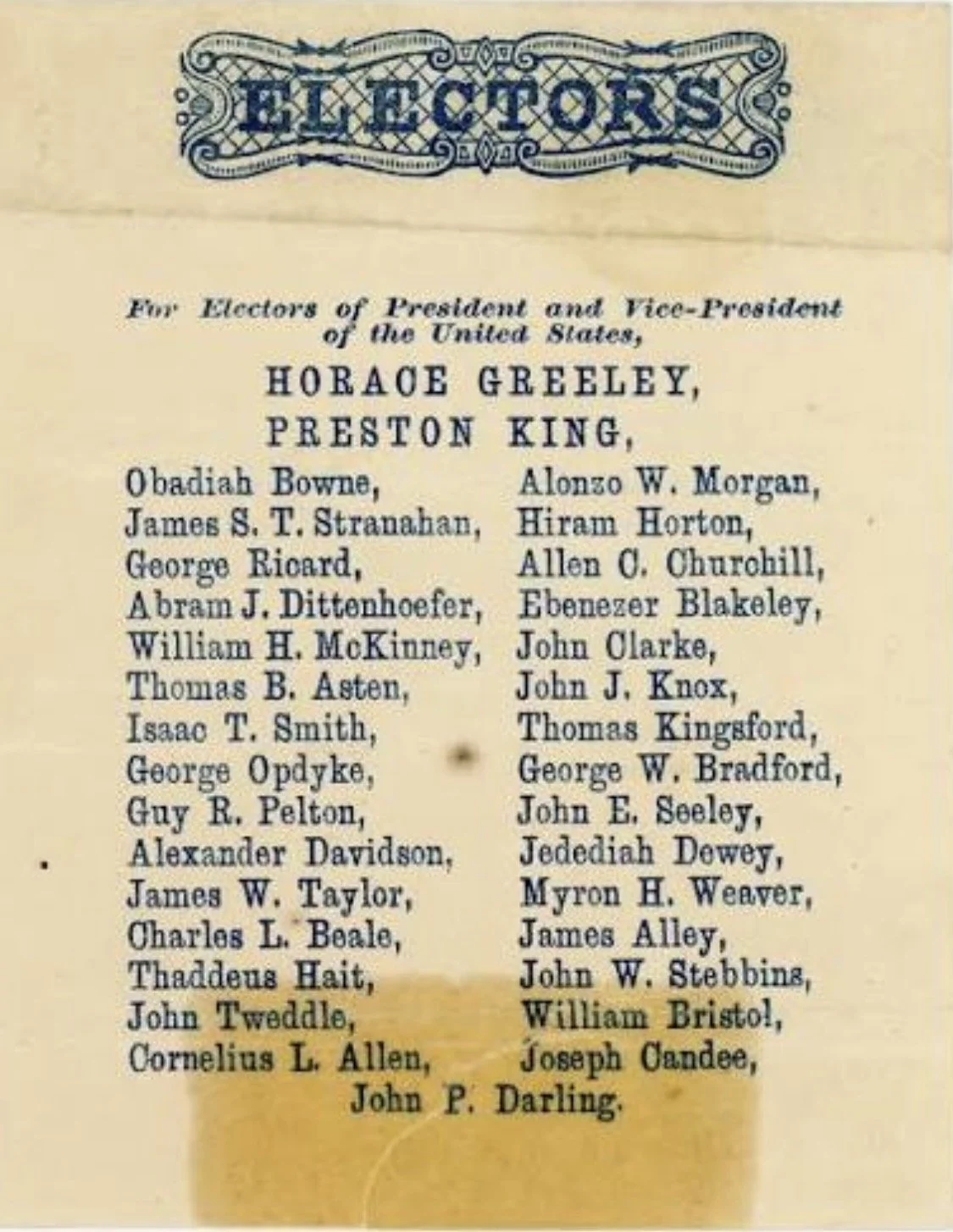

In the 1860 campaign, he stumped for the first Republican presidential candidate to stand a serious chance in New York. In 1864, he rose another rung: he served as a presidential elector, formally casting one of New York’s electoral votes for Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.

Half a century later, he would be celebrated as the last surviving Lincoln elector. It’s not every lawyer who can say, with literal accuracy, “I helped elect Abraham Lincoln.” Dittenhoefer could.

Lincoln appreciated him enough to offer him a federal judgeship, District Judge of South Carolina, after the 1864 election. Most lawyers would have leapt at the chance. Dittenhoefer politely declined, preferring his New York practice (and, perhaps, the prospect of not moving back to the state he’d spent his adult life politely disagreeing with).

A War President, Up Close

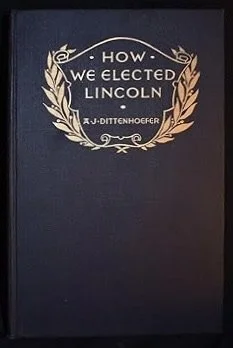

Dittenhoefer’s memoir, How We Elected Lincoln (1916), is part campaign history, part political gossip, and part affectionate portrait of the man in the White House.

He recalled visiting Lincoln with Illinois Governor Richard Yates to plead for the discharge of a hard‑luck officer. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had a blanket rule against such discharges, but Lincoln walked with them down the corridor and said, with mild mischief, “Mr. Stanton, in this case, it is the President’s order.”

On the way back, Lincoln turned to Yates and Dittenhoefer and, half‑jokingly, half‑tiredly, said that when it came to Stanton, he sometimes felt he “had not much influence with this administration.” He admitted he would love to return home to Illinois, but knew he had to “stick it out to the end.”

In another conversation, Lincoln gave Dittenhoefer what may be his most quotable philosophy on criticism:

“I do the best I can, and I mean to keep doing so until the end. If the end brings me out all right, what is said against me won’t amount to anything. If the end brings me out wrong, ten angels swearing I was right would make no difference.”

For a young Jewish lawyer who had defied his father, his party’s critics, and half his city to support Lincoln, those words clearly stuck. They appear in his memoir 50 years later with the clarity of a line he never forgot.

A Judge Who Gave Away His Salary

In 1862, New York’s Republican Governor Reuben Fenton appointed Dittenhoefer to the City Court to fill a vacancy created by the death of Judge Florence McCarthy. It was a plum appointment for a man not yet 30.

Dittenhoefer’s first major act as a judge was not a legal opinion, but a charitable one: he quietly gave his entire judicial salary to McCarthy’s widow, who had been left with limited means. When his term ended in 1864, he refused to run to succeed himself and returned to law practice.

On the bench, he earned a reputation for clear reasoning and impartial rulings. Off the bench, he earned a reputation for stubborn courage.

During the violent New York City Draft Riots in 1863, a mob advised him, rather strongly, to leave town. As a well‑known German‑Jewish Republican and Lincoln supporter, he was an obvious target. [Dittenhoefer refused to go][4]. It was not the safest possible decision, but it certainly broadcast where he stood.

[4]: A French Facelift - 17 East 83rd Street

Counsel to a City, And to the Theater

Back in private practice, Dittenhoefer built one of the most interesting legal résumés of his day.

He became known for several things at once:

• Counsel to the New York City Board of Aldermen and to multiple banks and financial institutions (including Lincoln National Bank and Franklin National Bank).

• A specialist in excise law, steering saloonkeepers, importers, and city officials through the minefields of 19th‑century liquor regulation.

• A formidable defender in politically sensitive cases, such as the famous “sugar scandal” investigations, when bankers and journalists were summoned before a U.S. Senate committee to explain irregularities in sugar duties and refused to answer incriminating questions. Dittenhoefer represented several who were indicted for their refusal.

• Counsel in customs and import cases, including prosecutions involving fraudulent importation of Japanese silks.

• A shrewd corporate and insurance lawyer, advising major companies and banks.

Yet he became best known for a niche that sounds almost quaint now: theater law.

The Lawyer Behind the Curtain

In an era when American copyright law struggled to keep pace with a booming entertainment industry, playwrights, actors, and impresarios needed a legal champion. Dittenhoefer became that champion.

He represented leading playwrights and theater managers, including members of the American Dramatists’ Club. He successfully litigated cases involving foreign works such as Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado, helping establish that American performances of foreign plays could be protected from piracy.

He also pushed for reforms beyond the courtroom. At the request of figures such as playwright George Howard, Dittenhoefer helped draft amendments to federal copyright law and to New York’s penal code that made unauthorized performances a crime rather than just a civil nuisance. For dramatists who’d been watching their work “borrowed” freely, this was a small revolution.

He also secured the incorporation of the Actors’ Fund, a benevolent organization still remembered today, and served as its counsel without compensation. For decades he was the go‑to lawyer when a theater company, playwright, or actor needed advice, protection, or rescue.

If Broadway ever had a patron saint of the legal profession, Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer would at least make the short list.

Winning a Case That Changed International Law

Not all his important work wore greasepaint. One of Dittenhoefer’s most significant victories came in a case that sounded obscure at the time but later shaped extradition treaties around the world.

An American ship’s officer named Rauscher had been extradited from Britain to the United States for murder on the high seas, but once he arrived, prosecutors decided to try him for a different offense: the cruel and inhuman punishment of a seaman. To the U.S. government, this seemed efficient. To Abram Dittenhoefer, it seemed illegal.

Appointed by the court to represent the indigent defendant, Dittenhoefer argued that a person extradited for one offense could not be tried for another without the consent of the extraditing country; a principle that had been bitterly debated between the United States and Britain for nearly fifty years.

The trial court rejected his argument. Dittenhoefer appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court; still acting without compensation, purely because the legal issue mattered.

In United States v. Rauscher, the Supreme Court reversed the lower court and agreed with Dittenhoefer: an extradited defendant could only be tried for the offense for which he was surrendered. That “rule of specialty,” as lawyers like to call it, quickly became embedded in U.S. extradition treaties with other nations and is still a basic principle of international criminal law.

Not bad for a case that began with a poor mate and a court‑appointed lawyer.

From, Innocents Abroad

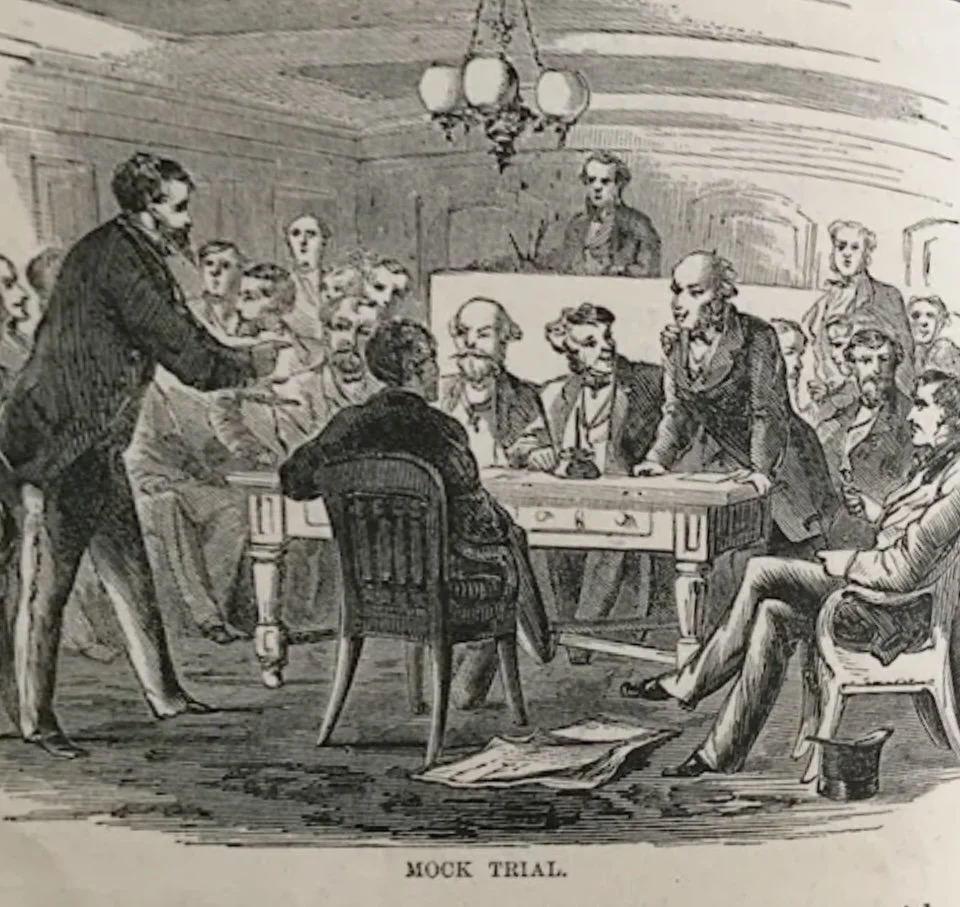

Mark Twain on Trial: The Most Unconscionable Liar in the World

For all that, the story that most people of his day remembered about Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer involves no great principle of law; just a great sense of humor.

On a transatlantic steamship voyage in the late 1800s, the passengers decided that the trip needed more entertainment. (Anyone who’s stared at the open ocean for six days will sympathize.) To raise money for the Seamen’s Fund, and to alleviate their own boredom, they staged a mock trial.

The defendant: Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

The charge: being the “most unconscionable liar in the world.”

The presiding judge: Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer of New York.

The jury was made up of earnest young students from Harvard and Yale; the witnesses were fellow passengers, nearly all more interested in jokes than justice. One testified, in all seriousness, that Twain was guilty because he had once said the coffee in Germany was weak. Others wandered off into unrelated matters with cheerful disregard for the indictment.

Twain defended himself with mock seriousness. The only difference between him and other people, he said, was that they were born liars; he had cultivated lying as an art.

The jury, unimpressed by this early attempt at “I’m just more honest about my dishonesty,” found him guilty.

Judge Dittenhoefer then pronounced sentence with a perfectly straight face: Mark Twain was ordered to read his own works aloud for three hours a day until the ship reached Bremen. Twain, who knew a cruel and unusual punishment when he heard it, declared that he would rather be hanged.

Ever the showman, he handed each juror a purloined napkin “to wipe away their tears” at his tragic fate. The event raised about $100 for charity, entertained the entire ship, and left Twain with enough material to embellish for years.

Newspapers later printed accounts of the trial. The idea that a New York judge once solemnly ordered Mark Twain to suffer through three hours of Mark Twain a day is probably the kind of judicial act Clemens appreciated most. Mark Twain later described the mock trial in The Innocents Abroad.

For all the playfulness, Dittenhoefer’s summing‑up was kind: he expressed the hope that Twain would “live long to continue to charm, instruct, and delight” the world. Coming from a man famous for serious legal work, it was a fitting tribute to an artist whose life’s work depended on both liberty and laughter.

Oddfellow’s Hall, Centre St, Manhattan

A Mason in the Metropolis

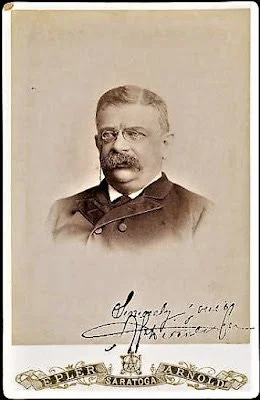

For readers of Astoriamasons.org, one part of Dittenhoefer’s life will hold special interest: his Masonic service.

Abram J. Dittenhoefer was a Charter Member of City Lodge No. 408, formed under the Grand Lodge of New York. The Lodge received its dispensation in 1855 and its charter in 1856. In its early years, City Lodge met in the historic Corinthian Room of the Odd Fellows Hall; still standing today at the corner of Centre and Grand Streets in downtown Manhattan, just across from the old police headquarters. As the oldest Lodge in the long line of mergers that now form Advance Service Mizpah Lodge No. 586 in Astoria, City Lodge No. 408 represents a proud chapter in our heritage. We honor Abram J. Dittenhoefer and the many brethren whose legacy continues to inspire us.

Abram J. Dittenhoefer was an active Freemason in New York. He served as Master of his lodge and rose to the statewide position of Commissioner of Appeals under Grand Master J. Edward Simmons. In that capacity he helped adjudicate internal Masonic disputes; a kind of appellate judge within the fraternity, relying more on equity, reason, and brotherly love than on statutory law.

His Masonic life dovetailed naturally with his public one. He believed in ordered liberty, in moral responsibility, in education as the path to improvement, and in the duty of the fortunate to assist those less fortunate; ideals that resonate with both his work for charitable causes (like the Actors’ Fund and seamen’s charities) and his quiet gestures, like donating his judicial salary to a widow or carrying an unpopular extradition case to the Supreme Court without pay.

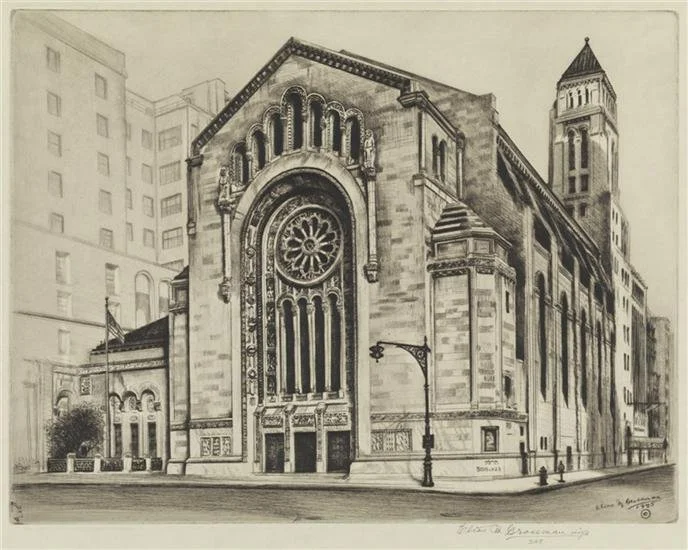

Temple Emanu-El, Manhattan

In civic life, he also served as a trustee of Temple Emanu‑El, New York’s leading Reform synagogue, and became a visible example of something still relatively new in the mid‑19th century: the Jewish American public figure who could move with ease in legal, political, Masonic, and religious circles without hiding any part of his identity.

The A. J. Dittenhoefer Warehouse, SoHo

The A.J. Dittenhoefer Warehouse

Located at 427 Broadway in SoHo, Manhattan, built in 1870, the A.J. Dittenhoefer Warehouse is widely regarded as one of the most distinguished cast‑iron buildings in the world. Completed in the 19th century, it anchors the corner of Broadway and Howard Street with magnificent façades on both sides, showcasing the elegance and innovation of New York’s cast‑iron architecture.

Its richly detailed façade,manufactured in cast iron and assembled on site, illustrates how 19th‑century builders blended industrial technology with high architectural style, a hallmark of SoHo’s iconic streetscapes.

Today, the A.J. Dittenhoefer Warehouse stands as a landmark of SoHo’s architectural heritage, a reminder of the neighborhood’s transformation from bustling mercantile district to one of New York City’s most sought‑after residential and creative quarters.

17 E 83rd, Home of Dittenhoefer during the poll riots

Letters, Addresses, and a Long Memory

Dittenhoefer’s address changed as his fortunes and the city evolved. Early on, he lived near West 34th Street and Eighth Avenue, in the hustle of a growing commercial district. Later he settled at 17 East 83rd Street, an elegant brownstone just off Fifth Avenue on the Upper East Side.

From there he wrote, corresponded, and reminisced. Surviving letters from him to Thomas Edison (in 1917) and from Theodore Roosevelt’s circle show the ease with which he communicated with the great and the inventive of his day. His downtown law address, 96 Broadway, across from Trinity church, placed him squarely in the heartbeat of New York commerce.

In 1916, at 80 years old, he published How We Elected Lincoln, ensuring that his memories of the 1860 and 1864 campaigns, and his encounters with Lincoln and other giants of the era, would not vanish with him.

Salem Fields, Cypress Hills

When he died in New York City on February 23, 1919, of a cerebral hemorrhage, he was widely reported to be the last surviving elector who had cast a vote for Abraham Lincoln. He was buried at Salem Fields Cemetery in Cypress Hills, which was established in 1851 by congregation Temple Emanu-el, and obituaries emphasized his legal achievements, his Lincoln connection, and his long service to the Jewish and civic life of the city.

Why Remember Dittenhoefer Today?

In a crowded 19th‑century New York full of big personalities, Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer sometimes appears in the background; the lawyer in the footnotes, the elector in the list, the judge behind the trial.

Look closer and a different picture emerges:

• A Southern‑born Jew who broke with expectation to join the anti‑slavery cause.

• A young lawyer who helped elect Lincoln and later captured the feel of that struggle in print.

• A judge who gave away his own salary to a widow and stood his ground during riots.

• A legal craftsman whose work still shapes international extradition law and theatrical copyright.

• A civic and Masonic leader whose life bridged synagogue, lodge, courthouse, and campaign hall.

• And, not least, a man who could preside with relish over the trial of America’s great humorist for the high crime of “unconscionable lying,” then sentence him to three hours a day of himself.

For Freemasons, Dittenhoefer’s life reads almost like a case study in the application of Masonic virtues to the rough‑and‑tumble world: fidelity to conscience over party or family pressure, justice tempered with charity, devotion to learning, and a willingness to stand by both principle and a good joke.

When we say that good men can shape history from lodge rooms, courtrooms, and even the deck of an Atlantic steamer, Abram Jesse Dittenhoefer is a name worth remembering: the judge who helped elect Lincoln and once tried Mark Twain, and who did both with equal seriousness of purpose and lightness of touch.