Was Brother Samuel Clemens’ Santa a Freemason? Or Some Illuminati Moon‑Lodge Schemer?

Pens, Aprons, and Parables: The Masonic Storytellers

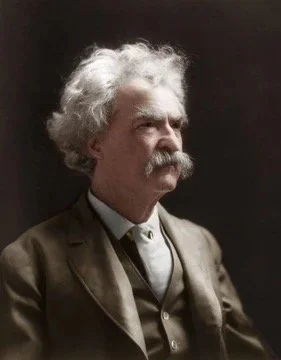

A certain river pilot turned truth‑seeker, Brother Samuel Clemens, may have taken a page from the writings of earlier Masonic authors; Brother Benjamin Franklin’s The Way to Wealth, Brother John Doyle Lee’s The Freemason’s Gift: A Christmas and New Year’s Offering, and Brother Rudyard Kipling’s poem The Mother Lodge, among others.

It’s a tradition carried forward by modern Brothers, such as Steve Chadburn in The Festive Freemason; blending wit, instruction, and the fraternal ideals of charity and moral refinement. But one can’t help wondering: is there something deeper threaded through their published works?

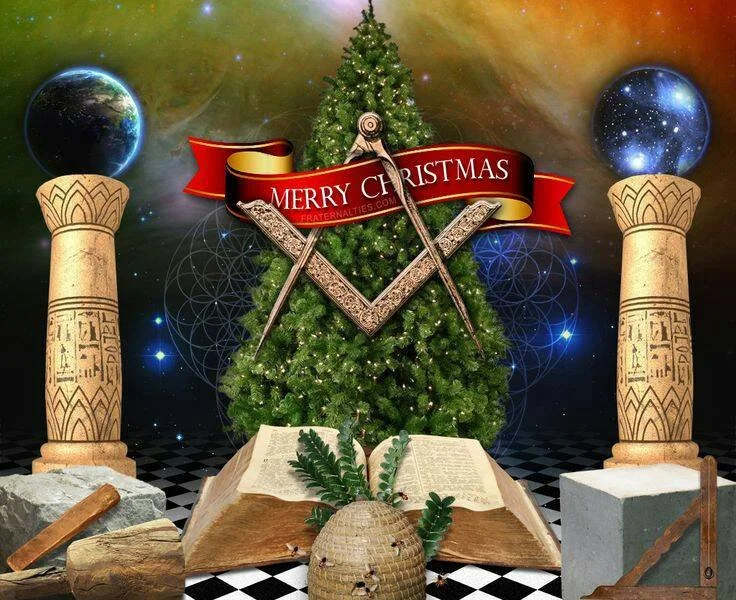

The Craft and Christmas: A Harmony of Light

Throughout history, many creative Freemasons have been inspired by Christmas themes, reaching back to the earliest days of modern music. Among the classical Masonic composers, Brother Felix Mendelssohn, Brother Franz Liszt, and Brother Georg Frideric Handel - who gave the world the Hallelujah Chorus and For Unto Us a Child Is Born - all celebrated the season’s sacred joy. Brother Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed Christmas Serenade, K. 398, while Brother Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 26, often called the “Christmas Symphony,” echoed the same reverent spirit.

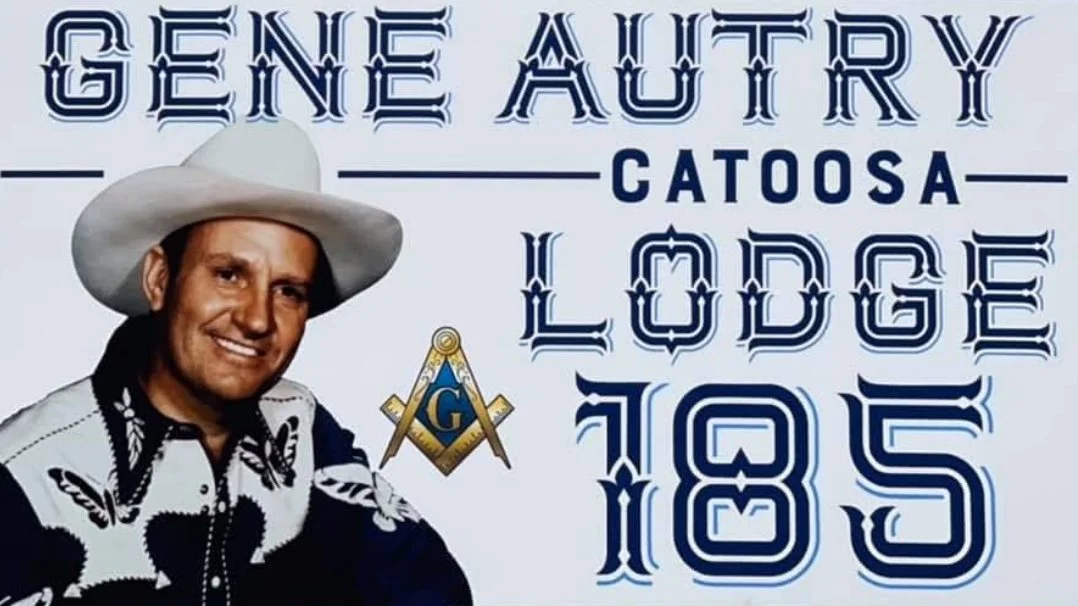

This tradition carried forward into more recent generations. Brother Irving Berlin gifted the world White Christmas. Brother Burl Ives lent his voice to A Holly Jolly Christmas and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Brother Gene Autry wrote Here Comes Santa Claus, among other holiday classics. And James Lord Pierpont, another Mason of melody, composed Jingle Bells.

What, one wonders, draws so many Freemasons to the Christmas theme? Perhaps it is the same call that moves every craftsman: to bring light, joy, and moral harmony into a waiting world.

From Parades to Pop Culture: The Deeper Masonic Threads of Christmas Continue

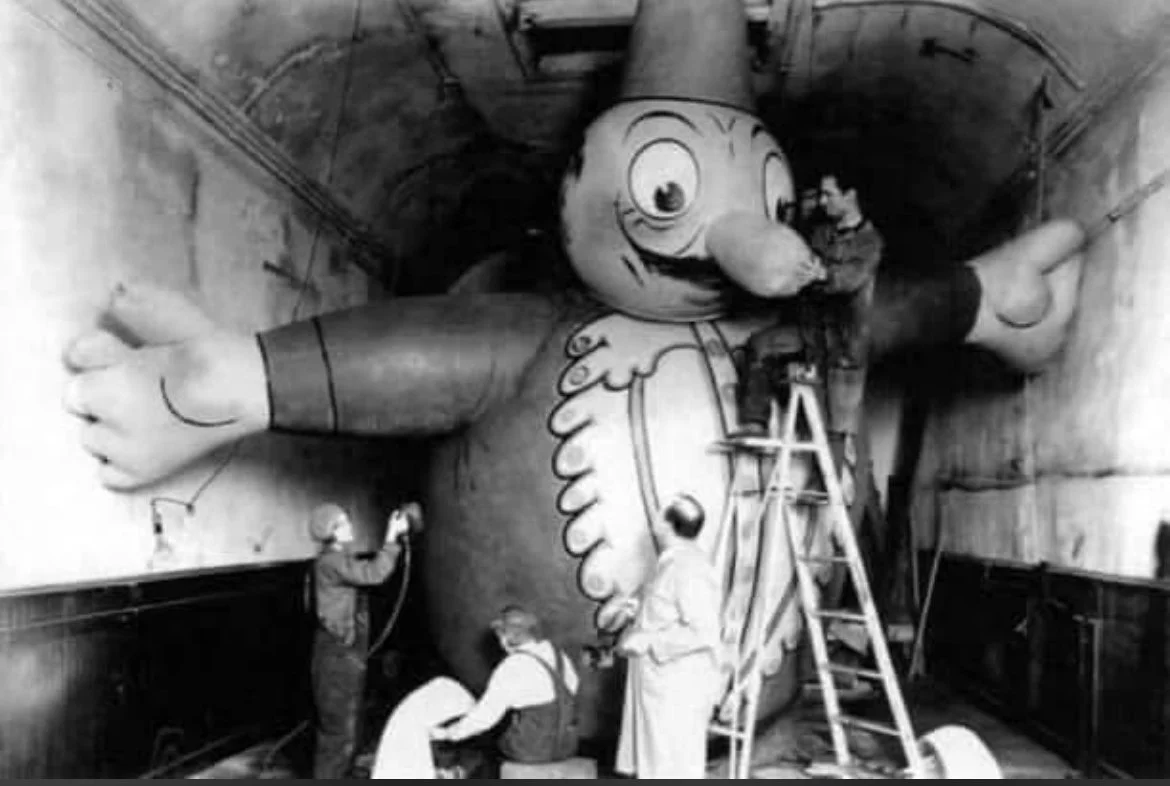

The connection between Freemasonry and Christmas runs deeper than music or literature. Brother Rowland Hussey Macy, founder of Macy’s, was himself a Freemason, and the spirit of the Craft quietly shaped the very traditions millions now associate with the season.

The original creator and designer of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloons, Brother Tony Sarg, was also a Mason. Several of his early balloon designs carried connections and symbolic ties to Masonic ideals. The Toy Soldier balloon was inspired by Brother Oliver Hardy’s March of the Wooden Soldiers, while beloved characters like Mickey Mouse and Goofy, creations of Brother Walt Disney, danced among them.

A Lunar Riddle: Was Twain’s Santa a Freemason in Red Flannel?

Now, gentle reader, pause with me a spell and ponder a riddle wrapped in a chimney. Cast your gaze upon a curious missive penned by that rascal Mark Twain, “A Letter from Santa Claus to a Little Girl.”

On the surface, it’s a merry tale from St. Nick himself, promising toys and cheer to a child named Susie. But hark! Beneath the tinsel and ho‑ho‑hos may lie a cipher worthy of the Ancients. Was the Santa Claus of Brother Samuel Clemens (that same mischievous wanderer we call Mark Twain) in truth a Freemason in red flannel? Or, perhaps, a higher operative in some celestial New World Order, whispering from a lunar palace while the lizard folk polish his sleigh runners?

Hush now, for the evidence piles higher than a stack of cordwood, and I shall dissect it with the scalpel of wit, until the truth twinkles like a trowel in moonlight.

The Lunar Lodge Address: Moon Base or Masonic Watchtower?

Let us first consider the fellow’s address: The Palace of St. Nicholas in the Moon. Not some jolly North Pole igloo, mind you, where penguins might peddle peppermint propaganda, but the Moon itself; that celestial body long whispered of in Freemasonic lore as the watchful orb above our winding stairs. “I live up here on the Moon,” he declares, as casually as a cat lapping cream.

Now, some folk (bless their hearts, wide shut) swear the Moon is hollow; a base for shadowy cabals, landing pads for reptilian overlords, or, at the very least, a fine backdrop for faking the Apollo landing. But why, then, does Santa choose to reside there, decoding “jagged and fantastic marks” from the scrawls of children? No ordinary alphabet for him! Nay, he reads the universal cipher of the stars.

Could these be the same symbols etched upon Masonic aprons and traced in Hiram’s lost word? Perhaps another hidden clue, stitched across Twain’s own writings; the author who once called the Moon “the eye of the night” and mused that “each man is a moon, with a dark side he shows to no one.”

One might even wonder if these children represent initiates in miniature; their holiday wishes serving as secret petitions for fraternal relief. Conspiracists, take note: Twain himself, the sharp‑eyed skeptic from Hannibal, was indeed a Freemason, initiated in Polar Star Lodge No. 79. Is the moon a nod to his mother Lodge? Was his letter merely a playful jest at our expense, or a breadcrumb trail laid for the truly enlightened?

Ritual Whispers: Blindfolds, Tiptoes, and Secret Tubes

But hark! More clues tumble from Santa’s sack like misplaced gavels. He demands blindfolds for George the butler, tiptoe silence lest death claim the careless, and whispers through speaking tubes; ritual oaths, anyone?

“Welcome, Santa Claus!” the child must cry, as if entering a lodge duly tyled against eavesdroppers. He descends the chimney, leaving boot marks as sacred stains: “Leave them there always, in memory of my visit.” Eternal reminders of the profane world, polished by brotherly labor.

And that trunk, filled with doll’s clothes; does he really mean aprons? Ordered in cipher, delivered discreetly under the piano like a chest of working tools. Coincidence? Or coded symbolism on a cosmic scale? The Bilderbergers may plot in Davos boardrooms, but this Santa, he conspires from lunar heights.

Reindeer Ciphers and Naughty/Nice Geometry

“Nay,” say the tin‑foil theorists, “’tis proof of the Masonic‑Deep State nexus!” Santa’s reindeer? Code for the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences. His list of naughty and nice? The Square and Compasses judging the rough ashlar. The elves? Junior stewards in green aprons. And that “Man in the Moon” alias? Surely a wink toward the Royal Arch’s veiled light.

The Whimsical Truth: A Craftsman, Not a Cabalist

Yet hold, dear friends and faithful companions; in Twain’s whimsical whirl, no sinister shadow hides. This Santa is Freemasonry personified: thoughtful, charitable, and radiating brotherly light. He reads beyond the veil of letters, delivers joy to the worthy, and teaches quiet lessons in generosity: whispering, “You need it more than I,” to some distant star‑child.

Those boot prints he leaves behind? Moral reminders for the wayward, not marks of mischief. Naughty? Repent, and point to the stain. Masonic? Indeed, in the truest sense, promoting light, brotherhood, and moral geometry amid life’s marvelous scribbles.

No moon‑lodge cabal here, but a merry Craftsman at work; troweling fancy upon the rough stone of the human soul.

Light of Truth

Yet hold your pitchforks, ye wide‑eyed theorists, for the true revelation lies not in shadows of the workshop but in the light of the lodge room. Twain’s letter, for all its moonlit mischief, glows with the essence of Masonic charity: benevolence unbound, joy bestowed without fanfare.

Like a faithful Brother, Santa labors in secrecy to relieve the wants of the less fortunate, answering distant pleas with gifts unwrapped by prejudice. It is pure, unadulterated giving; a living mirror of Freemasonry’s ancient tenets: Brotherly Love, Relief, and Truth.

Twain, ever the humanist, wove this fable not to mock the sacred, but to exalt the quiet heroism of anonymous generosity; proving that the real magic does not dwell in lunar lairs or cryptic codes, but in the open hand extended.

In A Letter from Santa Claus, Twain captures Masonic ideals through a playful structure rich in symbolism: secrecy, moral guidance, and brotherly kindness. As a known Freemason, he infused his whimsical Santa with the gentle wisdom of the Craft and its enduring call to light the world through good works.

Masonic Themes

Twain’s letter brims with ritual and mystery. His Santa enforces secretive protocols for his visit; blindfolds, tiptoeing, whispered exchanges through speaking tubes, and silence “under penalty of death someday.” These playful instructions mirror the structure of Masonic initiation rites and oaths of discretion. What begins as a child’s holiday fantasy unfolds as a symbolic journey of discipline, trust, and moral awakening.

Core Values Reflected

• Brotherhood and Charity: Santa praises Susie and her sister as “good children, well‑trained, and nice‑mannered,” rewarding virtue much like Freemasonry honors upright conduct and mutual aid.

• Moral Instruction: The boot‑stain left behind as a reminder to “be a good little girl” parallels the Craft’s use of symbolic tools and tokens to guide ethical reflection and self‑improvement.

• Universal Innocence: Santa’s reference to a universal “children’s alphabet”, understood by all across earth and stars, echoes Freemasonry’s spirit of inclusiveness, a brotherhood transcending language, creed, and border.

So whisper it in your Astoria halls this season: Twain’s Santa was no conspirator, but a Craftsman supreme: proving once more that the truest secrets hide in plain sight, tucked under the piano and dusted with a rag for the snow.

The Celestial Lodge: A Masonic Mystery

Could there be something deeper behind this story? If Santa Claus were truly a Freemason, one might wonder how he managed all that travel just to attend lodge meetings twice a month. Perhaps there’s something more. Freemasons have direct connection wirh the moon. Several members involved in the Apollo 11 moon landing were Freemasons. At least two of the astronauts to walk the moon have been Freemasons; Buzz Aldrin of Apollo 11 and James Irwin of Apollo 15.

On July 20, 1969, as part of the Apollo 11 mission, Brother Buzz Aldrin, acting under a special deputation from the Grand Lodge of Texas, claimed Masonic jurisdiction on the Moon. Three decades later, in 2000, the Grand Lodge of Texas formally chartered Tranquility Lodge No. 2000 in honor of that claim.

The lodge meets quarterly, which raises an intriguing question: why? Some might jest that it’s a clever way to help Brother Claus make his lodge visits without being detected by the ever-watchful eyes of modern technology.

Tranquility Lodge No. 2000 operates today, allowing Master Masons in good standing to join.

Merry Christmas, Brethren, and ever upward, the winding stair!